Prime

Heat wave: The cost of keeping cool in S. Sudan

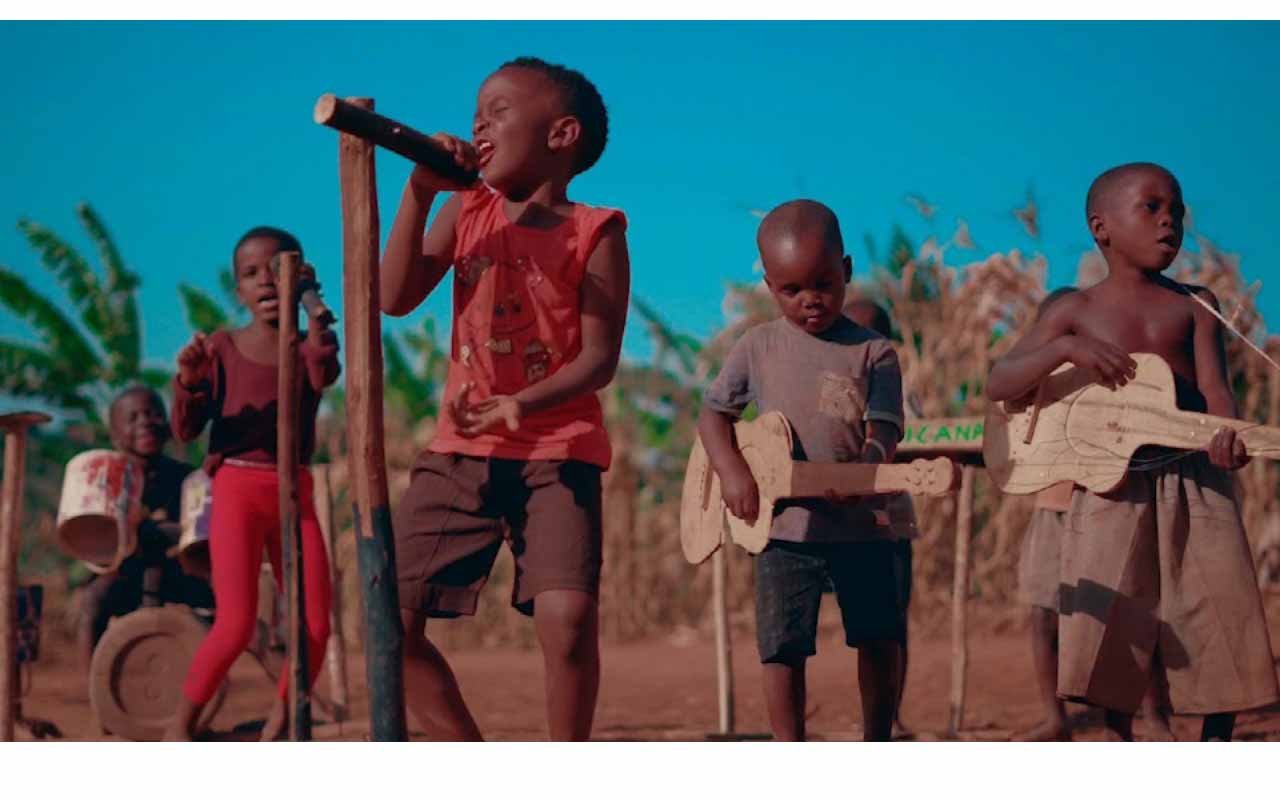

Parts of Juba city scorched by the burning sunshine. The heat waves forced government to close schools in the country. PHOTO/FRANKLIN DRAKU.

What you need to know:

- The government has closed all schools and parents have been advised to stop children from playing outdoors and monitor them for signs of heat exhaustion and heatstroke.

Last Sunday, a team of journalists from Kampala embarked on a 635-kilometre trip to Juba, the South Sudan capital city.

In Kampala, the temperature was 26 degrees Celsius (26°C), but up north in Gulu City, it soared to 31°C. But on the second day of our road trip to Juba, as we crossed the border at Elegu into Nimule on the South Sudan side, the temperatures had risen to 39°C.

As the day wore on, the heat intensified and by the time we arrived in Juba, the temperature had climbed to 42°C.

The residents in Juba say the blistering heat has confined them indoors for the last few weeks. They say they have only ventured outdoors at night when the temperatures climb down from 45°C to about 39°C.

So, on March 14, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry sounded the alarm bells. It warned the residents to spend their days indoors and avoid the blazing heat. The ministry also asked schools without cooling facilities to temporarily close until the sweltering heat comes down.

The ministry’s undersecretary, Mr Joseph Africano Bertel, said the heat wave in Juba and most parts of South Sudan will last at least two weeks.

“Excessive heat and humidity are becoming increasingly frequent, with high temperatures of 410C and up to 450C this week. High heat and humidity may cause heat stress during outdoor activity or extended exposure.

Extreme heat can also cause illness and death among at-risk populations such as seniors who cannot stay cool, infants, and those with chronic health problems or mental health conditions,” he said.

Mr Bertel asked the residents to take safety measures during this humid and hot period to stay safe. He said everyone should avoid strenuous activities, check on those most at-risk several times a day, including infants, young children, and older adults.

The environment ministry’s communication was swiftly followed by a joint communiqué issued by the Ministry of Health and that of Education that ordered the closure of schools on Monday.

The communiqué said the extended periods of high day and nighttime temperatures create cumulative physiological stress on the human body, which exacerbates the top causes of death globally, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease.

Health minister Yolanda Adel Weng said heat waves can acutely impact large populations for short periods, often trigger public health emergencies, and result in excess mortality, and cascading socio-economic impacts, including lost work capacity and labour productivity.

She said the disease surveillance department in the Ministry of Health has put a system in place to detect and respond to cases, as there are already cases of death related to excessive heat being reported in South Sudan.

Similarly, the acting Minister of General Education and Infrastructure, Mr Martin Tako Moyi, said the extreme weather condition poses serious health hazards to children, especially the young learners, and adults with underlying health conditions.

“The government has, therefore, decided to close down all schools with effect from March 18. During the closure, parents are advised to stop their children from playing outdoors, and they should monitor children, especially the young ones, for signs of heat exhaustion and heatstroke,” he said.

“Any school that will be found open during this time will have its registration withdrawn. The Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry will continue to monitor the situation and inform the public accordingly,” Mr Tako Moyi added.

The cost of keeping cool

In Juba, many businesses run on generators because of the high electricity tariffs. South Sudan has the lowest access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, with only 5.3 people accessing power, according to the World Bank. Only 1.8 percent have access to the national grid, while the remaining percentage use solar power and generators to power homes and businesses.

Swaib Luyima, a Ugandan trader in Juba, said: “We must buy ACs because fans cannot work here as they only blow. But the ACs are also expensive. Right now, businesses are struggling because we incur extra costs,” he says.

James Hotel, a four-star facility, is one such, running on diesel generators to cool the rooms and run other facilities. A staff member, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the hotel opted for generators because they could not afford the high electricity tariffs charged by the South Sudan Electricity Board.

South Sudan charges the highest electricity tariffs in the East African Community, with consumers paying 40 cents/KWh. This, they say, is due to reliance on expensive sources of energy from diesel generators and heavy fuel oil.

The World Bank says South Sudan has one of the lowest energy access rates in sub-Saharan Africa and in the world. While 46 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s population now has access to electricity, the energy access rate in South Sudan is estimated to be only 5.3 percent. Of the 5.3 percent with access to electricity, only 1.8 percent are connected to the grid, while 3.5 percent use off-grid technologies as primary energy sources.

For Deng Paul Chol, the situation has become unbearable. He said while the government is justified in asking schools to close, the situation in homes is worse, where many parents cannot even afford electricity.

“If a whole government we pay taxes to cannot afford the electricity bills to provide cooling facilities to the children in schools; where do they expect the poor parents to get cooling facilities from?” he asked.

The World Bank says lack of access to electricity makes the delivery of basic public services that are critical to addressing fragility, such as medical care, even more difficult. Most health and educational facilities outside of Juba do not have electricity. Even the higher-tier service facilities, such as state hospitals with diesel generators, provide very limited electricity services due to the high cost of transporting fuels to rural areas.

The World Bank says South Sudan’s transport infrastructure is unreliable and the numerous checkpoints on its major roads make fuel transport prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

The Bank also says lack of electricity limits the capacity of public health facilities to operate basic medical equipment, store vaccines at adequate temperatures, and provide an advanced educational curriculum, making it difficult to retain health care workers and teachers.

The government estimates that electricity demand, including unserved demand in South Sudan, is estimated to have increased to 800 MW in 2020, compared to an installed grid capacity of around 103 MW.

The off-grid installed generation capacity in Juba has been estimated at a total of 28.93 MW, which is almost as high as the installed capacity available on the Juba grid. About 99 percent of this off-grid capacity is generated from diesel, causing toxic emissions and noise, and only one percent is generated from solar energy.