Prime

The agony of a false HIV diagnosis

What you need to know:

- To AAR the patient contributed to his misery, that is, he was liable in contributory negligence as he failed to undertake routine short spell HIV tests as advised to establish his HIV status and his failure to return for follow up and review.

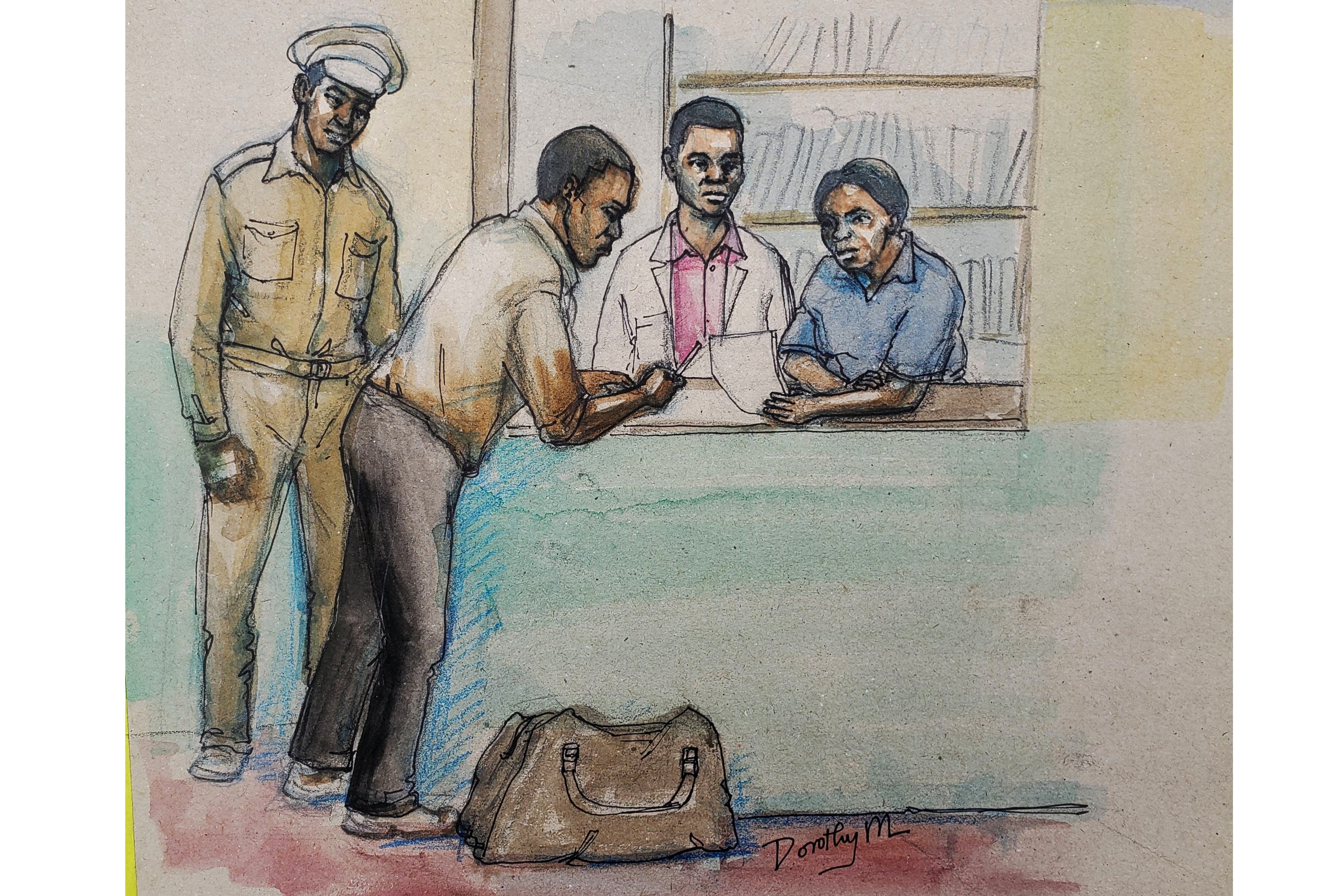

On March 29, 2007, Denis Okaka went for an HIV test in a laboratory belonging to AAR Health Services (Uganda) Limited.

The results showed that he was HIV positive and he was availed this results. Three months later the patient told court that he visited the same laboratory, as advised, and repeated the test, which still reflected that he was HIV positive.

This time round he was not availed a copy of the results and the reasons for this were not given. On November 17 that year the same laboratory carried out a CD4 count of the patient following the positive HIV test.

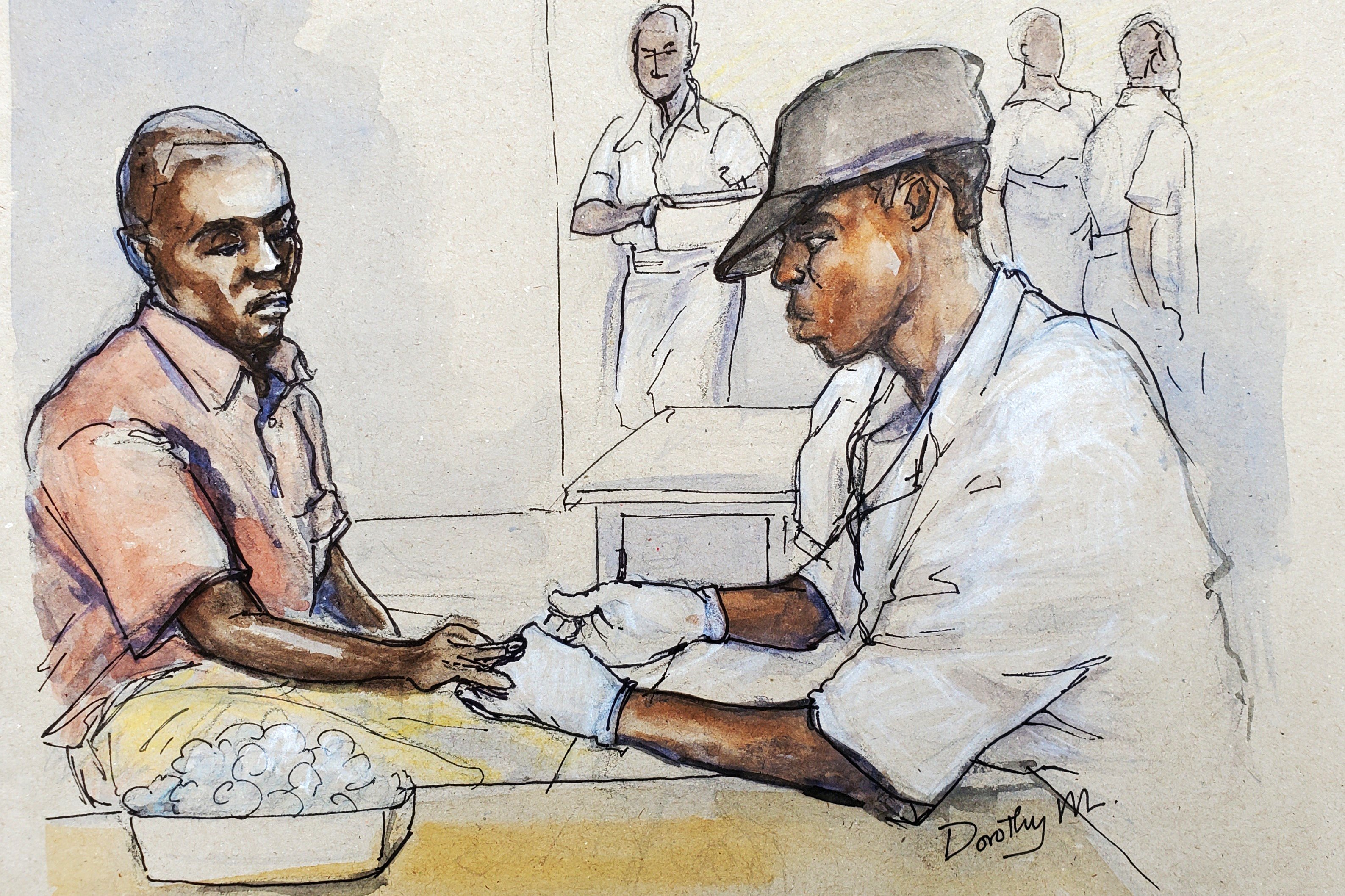

The CD4 cell count is a test carried out to establish the status of a person’s immunity in the setting of an HIV infection.

Tests negative

In May 2008, the patient developed difficulty in breathing and sought medical attention at Kampala Family Clinic where he was diagnosed with high blood pressure for which he was put on medication.

In the clinic the patient was found to have an undetectable HIV viral load in his blood and a near normal CD 4 cell count.

The clinic conducted three tests for HIV all of which turned out to be negative. The conclusion from the clinic was that the patient was HIV negative. This must have set the patient’s mind into the over-drive mode considering the anxiety and agony he had been put through.

Three years later, on 14th July 2010, the patient went back to recover his results from the AAR laboratory but the laboratory again failed to give him the results; this time the reason given was that the software in the laboratory had been overhauled and the previous laboratory results of all the patients were thereby deleted.

Civil suit

The patient, nevertheless, instituted a civil suit against AAR for medical negligence on December 17, 2014. The patient’s case was that as a result of the negligence of AAR’s laboratory staff he was twice diagnosed as HIV positive.

He, as a result, suffered grave emotional distress, loss of self-esteem, pain, anguish, embarrassment and loss of enjoyment of life all for which he asked court to award him Shs1b as compensation for the damages that he had suffered.

The patient’s lawyer submitted to court that the laboratory technicians employed by AAR failed to adhere to the medically stipulated procedures when carrying out the said HIV test on his client.

The procedures, issued by the Ministry of Health, on behalf of the Government of Uganda, are contained in a government policy document and supporting policy guidelines.

The procedure for HIV Counseling and Testing (HCT) in Uganda is contained in the Uganda National Policy Guidelines that was published in February 2005 and was in force in 2007 when the patient was tested. The policy document is entitled “The Uganda National Policy on HIV Counseling and Testing.”

Penalty

Failure to adhere to the guidelines was what led to the misdiagnosis of HIV infection in his client, the lawyer submitted. The guidelines provide for a procedure that is geared at ensuring that the results given to a person after testing represent the true HIV status of that person.

The lawyer told court that the laboratory staff did not follow the laid down procedure and as such, negligently failed to determine his client’s correct HIV status but instead gave him a false positive result. Ultimately, AAR was responsible for the wrongful actions and omissions of the people it employed in the course of their duties.

Not liable

AAR denied the patient’s claims and told court it was not negligent in the testing of the patient’s blood for HIV and that the company was not liable for any alleged acts of its officers as none of its employees ever negligently misdiagnosed the patient as being HIV positive.

AAR instead stated that the patient was advised of the need to undergo routine tests every three months but the patient chose to ignore this piece of advice.

To AAR the patient contributed to his misery, that is, he was liable in contributory negligence as he failed to undertake routine short spell HIV tests as advised to establish his HIV status and his failure to return for follow up and review.

AAR’s lawyer told the court that whatever was done by the laboratory to Okaka Denis in this case was clearly what any reasonable medical establishment would and should have done in similar circumstances. To the lawyer the guidelines that his colleague relied upon are not set in stone and AAR was at liberty to revise its own procedures to suit the particular circumstances as long as it remained within the confines of best practices of medicine.

In the policy guidelines the main target audience is policy makers and planners for HIV/AIDS programs and not the policy implementers such as his client. To him the relevant document applicable to a service provider was the Uganda National Policy Implementation Guidelines for HIV Counseling and Testing Services.

The lawyer further told court that there are so many test kits on the market that can be used to determine a person’s HIV status and that it was the laboratory’s choice and use of the Determine Abbot test was in line with the policy directives.

According to the policy the two testing methods recommended are alternate and it is not mandatory to use one over the other.

And as such a service provider cannot be faulted for using one accepted testing method over an alternative as had been the case here.

To be continued

Political goodwill.

Dr Sylvester Onzivua, Medicine, Law & You