Prime

Henry Kyemba, civil servant who exposed Amin's atrocities to the world dies

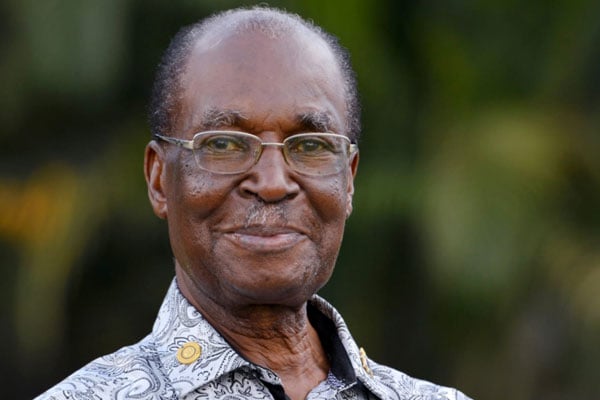

Former minister Henry Kyemba. PHOTO/ FILE

What you need to know:

- Throughout his life, Kyemba would maintain that the events of 1966, which would open the door to the 1971 coup, and condemn Uganda to decades of military rule, could have been avoided through dialogue

As Principal Private Secretary to the President, Henry Kyemba had the unenviable task of walking into the economy class section of the aeroplane to announce to the Ugandan officials onboard that Idi Amin had deposed President Milton Obote in a coup.

It was January 25, 1971, and the Ugandan delegation was flying back from a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Singapore. The plane was diverted to Mumbai, formerly Bombay where they conferred with Tanzania’s President Julius Nyerere who was loyal to Obote, before flying to the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

Here, Obote and his entourage weighed their options. Loyalist forces fled into exile and a rump of fighters would mass in southern Sudan to prepare for armed resistance. But in Kampala, the joyous response to the coup made it clear to Obote that the party was over, at least for now.

Kyemba had seen it coming. He had been at hand on February 22, 1966, when soldiers arrived in the Prime Minister’s complex to arrest Ministers Grace Ibingira, Dr Emmanuel Lumu, George Magezi, Balaki Kirya and Mathias Ngobi after their falling out with Obote. He had also witnessed, from close quarters, the unusual troop movements that culminated in forces commanded by Idi Amin attacking the Lubiri, the palace of the Buganda Kingdom, and driving the Kabaka, Sir Fredrick Muteesa, into exile in England.

LEFT: Mr Kyemba at his home in Jinja recently. He says he uses the shirt he is wearing only during interviews about Amin’s regime. Mr Kyemba adds that the shirt given to him by a medical friend in 1973 evokes memories of the Amin reign. Photo by Henry Lubega. RIGHT: Kyemba (L), Prince Mutebi (C) and Mayanja Nkangi in London in 1977 after fleeing Idi Amin’s government. The former Amin health minister and ex- PPS to Obote says he had to cover up events in his life so as to escape into exile in 1977.COURTESY PHOTO

Throughout his life, Kyemba would maintain that the events of 1966, which would open the door to the 1971 coup, and condemn Uganda to decades of military rule, could have been avoided through dialogue.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Kyemba turned to dialogue when, after a few days in Nairobi, and later in Tanzania where the entourage relocated, it became clear that Obote would not be returning to Uganda immediately, let alone as President.

Kyemba telephoned his office in Kampala and was told the city was safe and calm. President Amin, as he had since become, was not available. But the next call was put through to the new Ugandan leader, who immediately recognised him.

“Kyemba, come back; you are a government official,” Amin boomed down the telephone line. Then he added, cheekily, “By the way, what did you bring for me from Singapore?”

Members of the entourage to Singapore had melted away and Obote was left with just a handful of officials, including Kyemba, and his bodyguard. Kyemba was only 25 years old when Obote picked him as his private secretary and it was a difficult decision to leave. Obote eventually allowed them to return to Uganda and they flew back together to Entebbe where Kyemba hid the scared bodyguard’s pistols in his attaché case as they disembarked.

Photo moment. (L-R) Former Minister of Health Henry Kyemba, former Principal Judge James Ogoola, former Prime Minster Apolo Nsibambi and former Chief Justice Samuel William Wako Wambuzi share a light moment at the meeting last Friday. PHOTO BY STEPHEN WANDERA

With the change of guard, Kyemba half-hoped and half-expected to retreat to a quiet private life, but he was soon back in the saddle. First, Amin returned him to his old job as principal private secretary to the President. He was later transferred to the Ministry of Culture and Community Development as Permanent Secretary.

One day in November 1972 Kyemba was travelling to Nsamiizi, in Entebbe, where his minister, Yokosofat Engou, was scheduled to preside over a graduation ceremony. But the minister did not turn up. Halfway through the function, Kyemba was called to the telephone. Amin was calling.

Kyemba dutifully informed the President that he was at the function but the minister was a no-show. "No,” Amin said on the other side of the line. “You are the minister!” Engou’s sacking had just been announced on Radio Uganda.

That was the beginning of a testing and turbulent five years as a cabinet minister in Idi Amin’s increasingly violent and militant regime. Kyemba’s brother, Kisajja, was abducted, but he was powerless to rescue him even when he was in what was deemed to be a position of authority.

It was after his transfer to the Ministry of Health in March 1974 that the extent of his powerlessness fully dawned on him.

“It took another change of job and another five years for me to learn how impotent – and how dispensable – I really was,” Kyemba would later write.

The turning point was the murder on February 16, 1977, of the Archbishop of the Church of Uganda, Janan Luwum, and ministers Erinayo Oryema and Oboth Ofumbi.

“I don’t think many had thought that Amin’s madness could go up to that extent of killing religious leaders like Archbishop Luwum,” Kyemba would recall in an interview many years later.

“Many of us had thought that he could play with the Kyembas, and the like and so on, but to go as far as to take the lives of people in specific positions of leadership in the Church? I think really that was madness.”

Still friends. Archbishop Janani Luwum with president Amin and foreign dignitaries.

Kyemba’s mother ordered him to leave Uganda at the earliest opportunity. That opportunity came a few weeks later, in April 1977, when Kyemba travelled with the Ugandan delegation to the World Health Organisation’s annual conference in Geneva, Switzerland.

He began speaking out in articles in the Sunday Times of London on June 5 and 12, 1977, which drew the world’s attention to the extent of Amin’s brutality and deceptiveness. His first-hand account of the horrors he saw at close quarters all came together in a book, ‘State of Blood: The Inside Story of Idi Amin’, which was effectively a whistle-blower’s account of the violence and murders under Amin.

Pedigree of power

Henry Kisaja Magumba Kyemba was born on February 8, 1937, in Bunya County, in Uganda’s eastern Busoga region, into a family steeped knee-deep in local power and politics.

His grandfather, Chief Luba, was the traditional hereditary leader of Bunya County. He had earned his place in the annals of history by ordering the murder on October 29, 1885, of Bishop James Hannington of the Church Missionary Society whose decision to approach Buganda Kingdom from the dreaded eastern overland route was ultimately fatal.

Kyemba’s father, Suleman Kisadha grew up to become the chief of Nambale Sub-County in Mayuge District. His mother, Susana Babirizangawo, was the daughter of Daudi Kintu Mutekanga, one of the most eminent administrators and entrepreneurs to emerge from Busoga.

Mutekanga, a man of humble origins, had risen to become Prime Minister of Bugabula under Chief Yosiya Nadiope. He served as regent until Sir William Wilberforce Kadhumbula Nadiope came of age.

His brother, David Kisadha Nabeta, who had great influence over the young Kyemba, was Busoga’s first representative to the Legislative Council.

Kyemba attended local schools before joining Busoga College Mwiri for his Cambridge School Certificate, which he completed in 1956. He graduated from Makerere University with a history degree and hoped for a quiet life in the civil service.

But he could not escape the demands of the day as the country prepared for independence and pressed its best and brightest into positions of authority. Despite asking to be posted upcountry during interviews, the head of the civil service, Peter Allen, instead appointed him an Assistant Secretary in the office of the Prime Minister.

Henry Kyemba, the secretary of the Judicial Service Commission, chats with Justice James Ogoola. file photo

He was soon named coordinator of the National Symbols Committee, which had been tasked to develop the paraphernalia of the soon-to-be-born new country.

After independence, he was named private secretary and later principal private secretary to Milton Obote.

This gave him a front-row seat to the political manoeuvres the country’s first post-independence leader made to impose a republican order, despite being in alliance with the monarchist Kabaka Yekka party.

Those failed manoeuvres, and Obote’s decision to unleash the army under Amin to resolve the political disputes paved the way for years of violent political instability and military rule.

Kyemba returned to Uganda after Idi Amin was forced out of power in 1979. He kept a low profile until he was elected to represent Jinja West in the National Resistance Council in 1989, followed by his appointment as State Minister for Animal Husbandry.

He represented the constituency in the Constituent Assembly and in the Sixth Parliament that followed, before retiring from politics in 2001.

He continued to push quietly for a national dialogue while serving on the Judicial Service Commission, the Muljibhai Madhvani Foundation Scholarship Scheme, and in his beloved Rotary.

In the latter, he rose to serve as Governor of Rotary District 9211 which comprised Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Eritrea, Seychelles, Mauritius, and the French Union.

He was instrumental in securing and distributing over 200 volumes of encyclopaedias to schools in Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia as part of efforts to promote literacy and education.

He was part of Rotary International’s campaign, launched in 1996, to “kick polio out of Africa”. The declaration, on August 25, 2020, that Africa was free of the wild poliovirus left him beaming with pride. “Decades of extraordinary investment and hard work have paid off,” he told an interviewer.

Henry Kyemba died on October 19 from complications related to old age. He was 84. He is survived by two widows Betty Zalwango Kyemba and Janet Nabirye Kyemba. He is also survived by four children: Henry Kyemba Jr, Susan Kyemba Kasedde, Linda Nabirye, and Louis Kisadha Kyemba.