Prime

Mayanja bounces back after leading a strike at Makerere

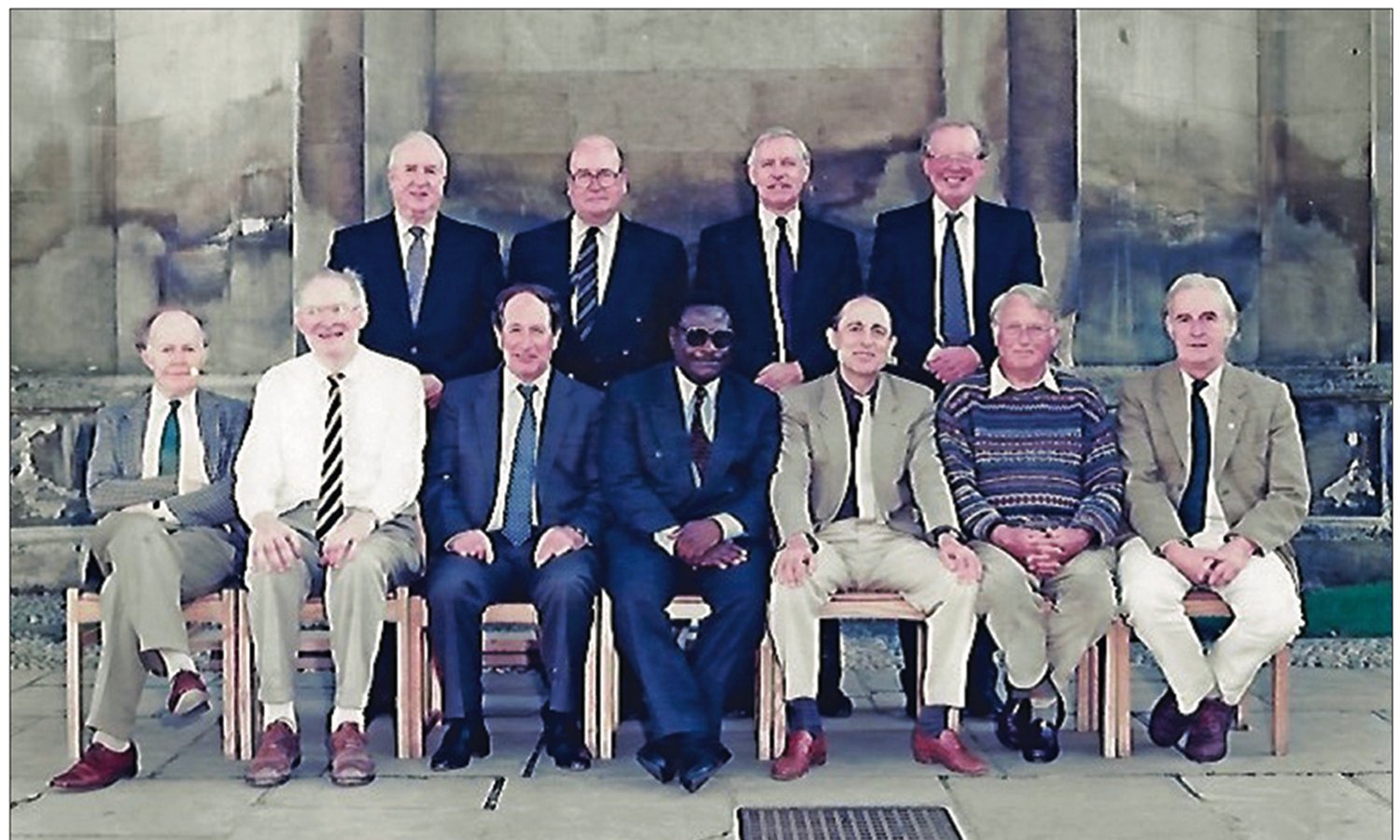

Mayanja and other guests at the Reunion Dinner of King’s College, Cambridge matriculation class of 1953. Photo/Courtesy

What you need to know:

In 1952, Abu Mayanja led a strike that broke a calm of 20 years of peace at Makerere University. Complaints about bad food at the ivory tower soon precipitated a vote of no confidence in the Student’s Council, then a mass petition, and refusal of students to eat and attend lectures.

When the dust settled, Abu Mayanja was expelled from the hill. In the third instalment of the serialisation of Prof ABK Kasozi’s book on Abu Mayanja, the historian describes how things started to look up after a bleak outlook.

In 1952, Abu Mayanja led a strike that broke a calm of 20 years of peace at Makerere University. Complaints about bad food at the ivory tower soon precipitated a vote of no confidence in the Student’s Council, then a mass petition, and refusal of students to eat and attend lectures.

When the dust settled, Abu Mayanja was expelled from the hill. In the third instalment of the serialisation of Prof ABK Kasozi’s book on Abu Mayanja, the historian describes how things started to look up after a bleak outlook.

After being expelled from Makerere College, Mayanja worked hard to find ways to continue with his studies.

He was fortunate because at the time when he was searching for where to go, top colonial officials were also searching for highly educated Africans who would cooperate with them in the management of the colonial state.

The 1947 Colonial Office’s “plan for decolonisation” envisaged working with and eventually handing over power to educated Africans instead of the traditional elites who had previously collaborated with colonial authorities in the management of African societies through the Indirect Rule (or “Lugardism”) system.

This change of policy increased the demand for educated Africans, and Mayanja’s luck came when one of the architects of that policy, Sir Andrew Cohen, came to Uganda as governor in 1952.

Cohen used to work as Under Secretary of State for Africa under Colonial Secretary Creech Jones. He thought that “clever nationalists (were at) a premium” in Africa, so he was ready to give Mayanja a scholarship to study in one of the “best universities” in the UK.

Although Cohen and top Protectorate officials expected and tried to make Mayanja appreciate and imbibe Western values, he did not immediately live up to what they expected of him.

Instead of focusing on his studies and attending British cultural attractions like operas, classical music performances or exhibitions in museums, Mayanja was involved in organising anti-colonial movements, attending political meetings, writing anti-colonial articles in newspapers and travelling to countries believed to detest Western values, such as the USSR, Burma, China, Egypt and India.

By the time he settled down in Uganda in 1959, colonial officials like Governor Sir Frederick Crawford, were no longer interested in him, and the latter refused to meet [Uganda National Congress] UNC officials if Mayanja was part of a delegation.

Fighting the dark horizon

Like many expelled students, Mayanja found himself alone as soon as he exited the educational institution he wanted to recreate through a strike. His peers, who had cheered him on as the leader of the strike, were no longer around to support him.

As a rebel, he was not likely to get a job in the government or in respectable private firms. He could work at [Ignatius] Musaazi’s Office of the Federation of Partnership of the Uganda African Farmers (the Federation).

However, “the Federation” was not a rich organisation, and any salary it could afford to give him would not satisfy his needs.

As he later wrote to CH Hartwell of the chief secretary’s office at Entebbe, “the horizon was for me very dark, and I had hardly any prospects at all.”

However, Mayanja was an energetic young man. He decided to move forward instead of merely licking his wounds.

He sought immediate advice from one of his admirers and mentor, Bishop C Stuart, who was about to retire as the head of the Anglican Church of Uganda.

Mayanja did not reveal how and why he became so close to Bishop Stuart, but the relationship most likely started while he was still at Budo.

The bishop advised him to repent and apologise to the Makerere authorities and tutors to get recommendations from them for either further studies abroad or readmission to Makerere College.

He met the principal and apologised. As for a scholarship, he approached the Buganda government for help. Although he was considered an opponent of the Mengo establishment because of his association with Musaazi, this did not deter him.

He went to see Mr Latimer Mpagi, the Omuwanika (treasurer) in the Kabaka’s government. The latter promised to speak to the Kabaka if Mayanja would bring favourable letters of recommendations from his former tutors at Makerere.

Handy support

Luckily for him, many of the tutors at Makerere College were willing to help. Several of them, including Principal Bernard de Bunsen, agreed that the students had a point in demanding to be heard, even though the staff did not approve of the methods used.

Most of the staff realised that the food was not good, as de Bunsen himself admitted years later. Dean of Students Alistair Macpherson lost his job, as did Florence Ford, the head of cooks, because of their ineptitude.

As noted in his letter to the senior tutor of King’s College, the governor, Sir Andrew Cohen, also concluded that the students had grounds for complaining although the methods they used to communicate their views were not seen as the best.

Moreover, a few professors, including Kenneth Baker, lamented the loss of their most brilliant students.

The cover of Prof ABK Kasozi’s new book on Abu Mayanja. PHOTO/COURTESY

Thus, Mayanja was able to receive recommendations for further studies from several Makerere academic staff, especially those in his faculty, including AG Warner, Kenneth Baker and Kenneth Ingham.

Armed with these letters of recommendation brought to him by Mayanja, Latimer Mpagi talked to the Kabaka about Mayanja.

The latter was hesitant because he considered Mayanja a rebel who was working with the critics of Mengo, then led by Musaazi.

However, Prince Badru Kakungulu put in good words for Mayanja to the Kabaka and the latter spoke to the governor about the issue.

Prince Badru Kakungulu said that the moment Sir Andrew Cohen was briefed on Mayanja’s case by the Kabaka, he immediately contacted Bernard de Bunsen for more information.

The latter gave him a very good report of Mayanja and told him that Mayanja was the most brilliant student in the Faculty of Arts and had won the governor’s meritorious academic prize in 1951 on the arts side in the intermediate examinations (in Mathematics, History and English).

By a stroke of luck, a delegation of the Uganda National Congress consisting of Musaazi, Abu Mayanja, S Abongwato, S Katamba, EN Bisamunyu and E Olyech went to meet the governor in September 1952 on political matters of the colonial state.

Sir Andrew Cohen was so impressed with Mayanja that when recommending him to the senior tutor at King’s College, Cambridge, noted that: “[Mayanja] had great charm of manner and I thought considerable personality. de Bunsen knows him well and has a real liking for him and belief in him.”

Horizon begins to brighten

In a meeting with de Bunsen, Protectorate officials who were led by the office of the chief secretary decided (a) to find a place for Mayanja in one of the best universities in the UK, (b) to give him a scholarship from the £200,000 funds earmarked for training African civil servants, (c) to take up Bishop Stuart’s offer of being Mayanja’s guardian while the latter was in the UK and (d) to prepare him to work in the Cooperative Department or as a teacher and, eventually, to have him become the headmaster of Kibuli Secondary School.

The officials hoped that Birch, the Resident of Buganda, would ask the Buganda government “to keep its hands-off Mayanja.” Governor Sir Andrew Cohen threw his weight behind this venture. As an old student of Cambridge, he did not bother to write to Oxford.

Instead, he wrote to the senior tutor at King’s College, Cambridge—LP Wilkinson—to have Mayanja admitted. The records do not show why Sir Andrew Cohen chose King’s College instead of Trinity College, where he had studied and got a double first-class degree.

In a four-page letter dated October 14, 1952, Sir Andrew Cohen started his communication as follows: “I am venturing to write to you to find out whether King’s would be prepared to help us in the following matter.

We have a rather brilliant history student here, AMK Mayanja, and I am anxious to find out whether there would be any chance of the King taking him in October 1953.”

[Adding:] “The circumstances are not easy, as Mayanja has recently been sent down from Makerere because he took the lead in organising a strike against the College authorities a couple of months ago. I will give you the background.”

He went on to give reasons why Mayanja should study at Cambridge. First, Mayanja was far more brilliant than his peers at Makerere. He needed to be at King’s College, where he would be met by his intellectual equals.

Although Cohen did not know Mayanja well, he observed his excellent performance when a [UNC] delegation met him.

Finally, he thought that it would be good for Uganda to have educated politicians, adding the following: “In colonial society, where clever nationalists are at a premium and where all sorts of pressure are liable to be put on them, his good qualities may well be damaged unless they are made use of.”

On the other hand, [he proceeded to note,] “I believe that potentially, he has the most valuable qualities which we ought to give the greatest possible chance of developing”. Adding that: “[…] it is important from the point of view of Uganda that we should” educate Mayanja.

[Governor Cohen] also informed Wilkinson that the retiring Bishop of Uganda, C Stuart, who was going to take up a position as the Assistant Bishop of Worcester, was prepared to be Mayanja’s guardian if the latter went to the UK.