Prime

Museveni’s childhood friend goes to rest

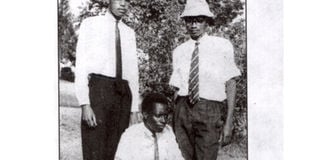

Eriya Kategaya (L), President Museveni (R) and Mwesigwa Black at Ntare School in 1965. COURTESY PHOTO

What you need to know:

Fallen First Deputy Prime Minister Eriya Kategaya shared a 40-year friendship with President Museveni.

KAMPALA

Such are childhood friendships that many never measure up to anything. They blossom in the innocent excitement of infancy but often fizzle and die away when maturity and all its burdens set in.

A few childhood friendships, however, defy this natural rise-and-fall trajectory. They instead increase in magnitude and intensity of bond, gathering common value systems long the way. History will judge the life of Eriya Tukahirwa Kategaya, a seasoned politician and qualified lawyer, through the eyes of the latter form of childhood friendships. His was a life defined by his relationship with Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s president since 1986.

The two were acquainted in 1953, as pupils at Kyamate Primary School, in Ntungamo District. This acquaintanceship grew into a stronger bond of friendship when the two met again in Mbarara High School and again at Ntare School. Through university in Dar-es-Salaam, exiles in Kenya and in Tanzania, the armed struggle, through to capturing power and efforts at creating a functional state and economy, it continued to grow in leaps and bounds.

Like all friendships, there were bumps in the road, in this case a fundamental disagreement on political ethics and value systems when Museveni orchestrated the amendment of the Constitution in order to run for re-election in 2006.

Stunned by the volte-face, Kategaya spoke out and immediately paid the price when he was fired from Cabinet. In the end he came off as the innocent half of a friendship, the idealist who learned the hard way that scholars of political hardball and realism like Thomas Hobbes and Niccolo Machiavelli were right after all – in politics, virtue does not win; shrewd political manipulation does.

His death

Mr Kategaya died on Saturday evening at Nairobi Hospital of a condition known as thrombosis, or a blood clot. By the time of his passing, he was Uganda’s First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for East African Community Affairs. His death brings to an end a career, which, save for the three years he was thrown out of Cabinet, was spent working and fighting for his country in one form or other.

Kategaya had an outstanding and unmistakable sense of injustice. He smelt it a mile away and turned his nose to it almost immediately. This side of his character was already showing itself in high school at Ntare when during the mid-1960s, then Prime Minister, Dr Apollo Milton Obote, fired and arrested five cabinet ministers and later suspended the Constitution.

Kategaya, with friends who included Mr Museveni, marched up to the Prime Minister of Ankole, James Kahigirizi’s office, demanding to know what he would do to oppose Dr Obote. Mr Kahigirizi told them to “take it easy”, and that sunk their morale with disappointment.

Despite this drive, he chose to study law and became a political activist, two fields not known to make a case for genuine justice. This contrast was no better illustrated than in 2003, when his 40-year-old friendship with Mr Museveni, drove off the cliff and plunged into the abyss.

Mr Museveni chose to seek re-election and to change the Constitution to make this possible. Kategaya found this a fundamental betrayal of the original values on which their political movement, started in high school decades earlier, was based. He did not hide his disappointment. “I have realised that the more one stays in power, the more one is insulated from reality,” he told a Parliamentary Advocacy Forum (Pafo) meeting on May 8, 2003. “The trappings of state apparatus tend to make one live unrealistic existence,” he added.

In an interview with the New Vision on May 18, 2004, he said: “What I am opposed to is the culture of not wanting to go away. All along I trusted President Museveni whenever we agreed on what to do but the kisanja [re-election-by-all-means] project has shaken my faith and trust in leaders...It seems the survival instinct overrides everything else.”

Right then, it seemed, Kategaya’s bubble of political idealism was brutally burst. He seemed to be realising, too late, that one could either choose to have selfless service or politics, but not both.

The result of this very public falling out was a very ungracious sacking from cabinet on May 23, 2003. Gone was all the status and prestige African cabinet ministers are known to wield like a government SUV with police escorts. The next three years were spent in near-oblivion, a time during which he attempted to revive his law practice.

It was during this time that he published his memoirs, Impassioned for Freedom (2006). The book clearly charted the journey that he and Yoweri Museveni had taken through school, war, government and on to their moment of disagreement. But six months after this publication, Kategaya was on TV lining up to accept a cabinet position in the very government he accused of being “money-crazy, (and a) mobcracy (leadership by the mob).”

U-turn

It was the ultimate U-turn. Had Kategaya yielded to the “if you can’t beat them, join them” mantra?

Commentary abounded on why Kategaya had chosen to serve a government he had discredited. The most persistent of these was that the three years spent away from a cabinet position to which he had grown accustomed for two decades, left him financially troubled. But when a TV journalist confronted him with a question about this, Kategaya replied, “That is a very stupid question.”

Although Kategaya returned to government, he was never the same man. The urge, verve and enthusiasm of old did not return. He was given the East African Community Affairs docket. The ministry put him in charge of a subject that was close to his heart (he played a key role in the resurgence of the EAC in 1999 as cabinet minister), but also, kept him away from troublesome ministerial beats that would push him right into the middle of political pushing and shoving.

Another radical change in ideology was his and Museveni’s rapid switch of heart from socialist-leaning politicians to becoming some of the strongest proponents of Western capitalism, almost overnight. Although Kategaya said the state-run economy’s inability to ensure efficiency opened their eyes to the benefits of capitalism, one cannot ignore the influence of IMF pressure that was rising on poor countries seeking funding in the late 1980s.

The influence of politics on Kategaya started during his days at Ntare School. His political ideologies were influence by Patrice Lumumba (he once grew a goatee to look like Lumumba), Frantz Fanon who wrote the Wretched of the Earth, Che Guevara, Chairman Mao of China and Karl Max, among others.

Kategaya was a man who grew straight out of the humblest of origins (he bought his first pair of shoes at 18). His ability to rise into the country’s political elite is largely in debt to his parents who defied pressure from relatives and funded their son’s education.

He was a down-to-earth man who did not let his “revolutionary credentials” wash all over him. While he had a son studying at Lohana Academy in the late 1990s, Kategaya would sometimes come over to pick him in a light brown Mitsubishi Pajero. And he often took the time to greet the children who recognised him and came over to greet him.

In his memoirs, Kategaya wrote: “In Africa, but particularly in Uganda, we seem to be cursed with having leaders who cannot be taken on their word.” For a man who started opposing bad leaders in 1970 to say this, nearly two decades after his friend and comrade was in power, seemed to suggest that all his efforts had gone to waste. In fact, the statements made him come off as a man who partly regretted having struggled for good governance in Uganda.

Ever the idealist, Kategaya did not leave things with a negative outlook. His efforts, and those of other people, would one day come to have their full effect. “The young men and women who left their studies to go to the bush to fight for the liberty of their people and those who gave their lives in course of the struggle did not do so in vain. What we are witnessing is a temporary setback...The world has also changed and the days of suppressing people without someone somewhere making noise of concern is gone.”

The relationship between Kategaya and Museveni was of a rare kind. Its course went through the warmth that friendship brought and the bitterness that was bred by disagreement. But its importance will never be lost on us. For it is not every day that two boys ever grow up to change the direction of their country like these two did.