Prime

Monitor at 30: It will die with Uganda’s deepest secrets

Author: Charles Onyango Obbo. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- The day before the raid, I got a call from an aide to President Museveni who said the Big House was livid about the story, and we were likely to get a whacking for it, so we should prepare ourselves.

The Monitor celebrated its 30th birthday on Sunday, having been founded by an idealistic, even benignly naïve, group of us on July 24, 1992.

The anniversary reminded me that while, over the years, the story of The Monitor has been told, the “real deep” stuff that we will probably take to the grave with us. They are secrets that might never be shared. If the country knew how many ministers stepped out of a Cabinet meeting, or senior UPDF officers who took advantage of a bathroom break to leak the proceedings of an ongoing High Command meeting that was being chaired by President Yoweri Museveni, it would be shocked to the bone. But the revelation would also probably lead to many people’s harm or even death.

One of the stories that got The Monitor shut down for about a week was corroborated by a senior UPDF officer. We got in big trouble. During the trial, one of the key state witnesses was our source! So we stood there in the dock, him across in the witness stand saying we were liars.

He gave us a knowing look that said, “guys, you must understand why I have to do this. You must have my back. If they found I corroborated this story, I am a dead man”. We were acquitted. What do you think happened after the trial? We became even better friends.

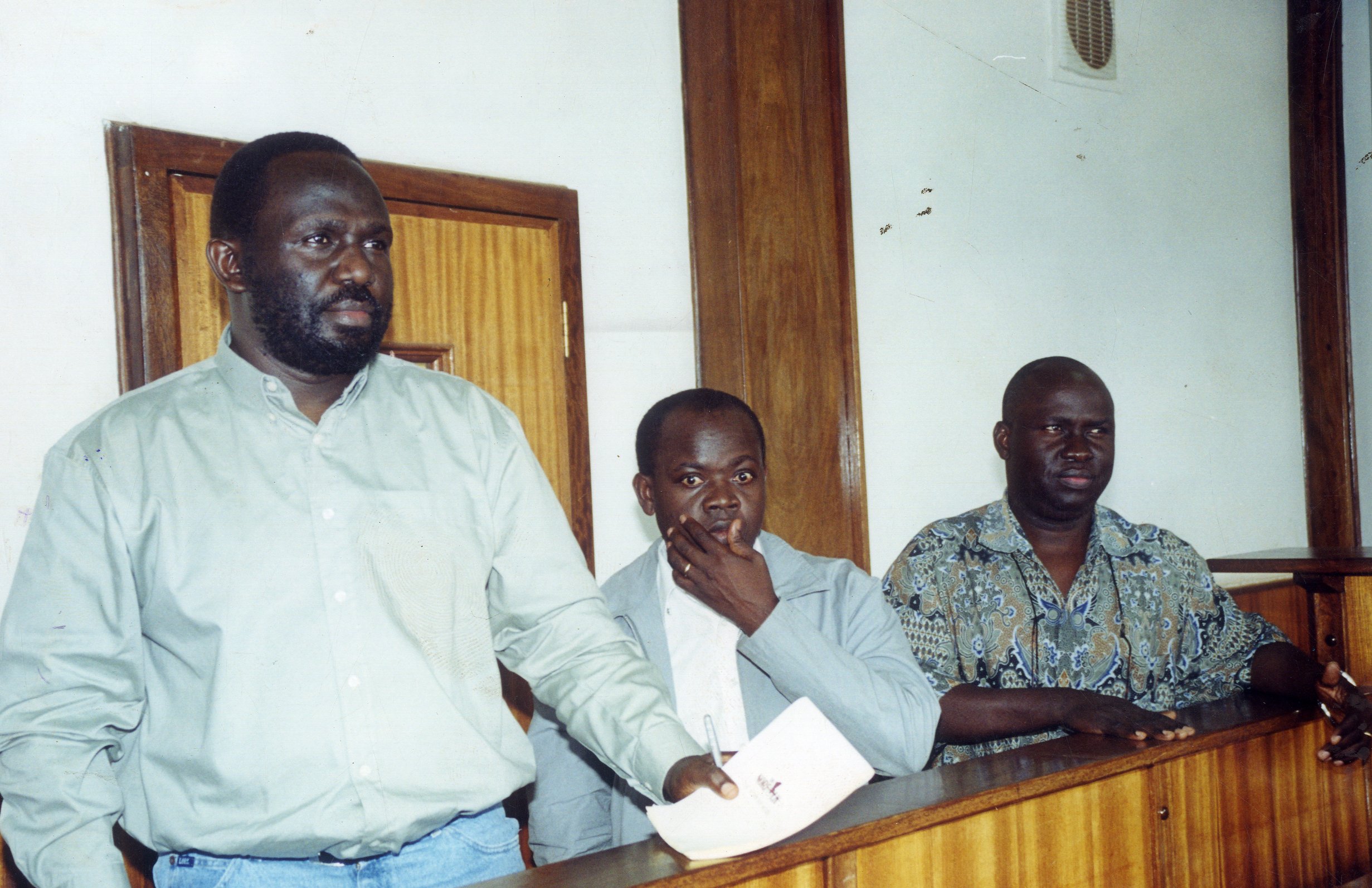

In October 2002, we got into trouble again over a story alleging a military helicopter had been shot down in northern Uganda. The Monitor offices were raided and shuttered for days, and we were hauled off to court.

The day before the raid, I got a call from an aide to President Museveni who said the Big House was livid about the story, and we were likely to get a whacking for it, so we should prepare ourselves.

Earlier in the day, we got wind of the fact that a raid was likely. A few people managed to cart away sensitive documents so that when the raid came that evening, the material that could have caused havoc to sources was safely out of the building.

When the raid happened, I had gone to meet then Local Government minister Jaberi Bidandi Ssali at his Kiwatule Recreation Centre when the call came that security forces had surrounded our offices. Bidandi asked if I needed help. I said no, and drove back to Namuwongo. On the way, a minister called and said I shouldn’t go back to the office. “They will torture you this time; we can arrange for you to get out of the country tonight”, he said. “No, thank you”, I replied.

Shortly after I arrived at the office, security let the rest of the staff go home. It was coming to about 10:30 pm. Three of us remained with them as they searched and seized documents and computers. They let us go home around 2 am.

Two days later, a staunch pro-NRM businessman called and asked me to go and pray with him at Christ the King at 1 pm. He insisted I must go. It was strange, but I went, made the sign of the cross, knelt, said a short prayer, and sat. He was nowhere in sight. He came in 15 minutes later and asked me to follow him.

He walked to the altar and through a side door into the vestry. He told me to wait and disappeared through another side door. He returned about 10 minutes later, and he was chatting away excitedly on his mobile phone and handed it to me. I nearly collapsed when I found out who was on the other end of the line. He was one of the country’s top leaders, and we had known him as generally anti-Monitor. But apparently, unknown to us, a couple of stories we had done in the past had saved his neck and helped him solve his political problems.

He said no harm would come to us. We should cool off our heels for four or so days, but the Monitor would be reopened in less than 10 days. And so it was.

And these are not the most dramatic of these events. It was a great and immensely valuable education about Uganda. Uganda is five times less monolithic politically than it appears on the surface. Then, no matter how dire the situation is, there are people – might be fewer these days - in the political system who will discreetly break in a progressive and liberal direction. Regime loyalty is very thin. Many “political fanatics” are mostly cold calculating cynics and pragmatists. What many of them do, isn’t always what they are.

Some of the richest Ugandan histories of the last 30 years, then, is in the story The Monitor hasn’t told yet, but still lies deep in its memory.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist,

writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. Twitter@cobbo3