Prime

Uganda has lost the dividend of Amin’s disaster

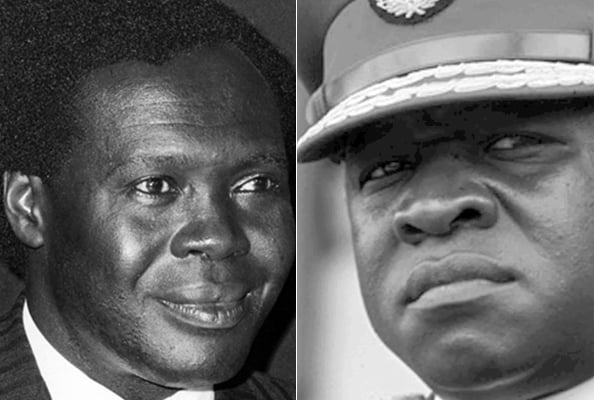

Author, Nicholas Sengoba. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- Today, under President Museveni’s ‘democratic’ dispensation, it is feasible to think about mobilising and demonstrating. While demonstrations don’t achieve much apart from having a nuisance value and making headlines, they were unthinkable in Amin’s days. Then, there was no pretence about democracy.

Currently there is an uproar concerning increasing prices of most food items and other necessities, especially fuel.

The politicians and economists have blamed it on the war between Russia and Ukraine which has affected the price of oil.

To many people born in the 1980s and beyond, this situation is shocking. The children who lived in the 70s during the regime of Uganda’s third president, Idi Amin Dada (1971 - 1979), have experienced it. The economy suffered seriously when the Asians were expelled by Amin in 1972. Production went down as a number of industries broke down and collapsed.

Then came the embargo intended to isolate Amin, for human rights abuses and a list of other ills. At one point Amin fell out with the Kenyan government and they sealed off the border. This stopped the flow of fuel and other commodities to landlocked Uganda. Tanzania was not an alternative, as President Julius Nyerere was an enemy.

So like the good book says in Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun. What is distinct is the way people responded to the crisis.

Today, under President Museveni’s ‘democratic’ dispensation, it is feasible to think about mobilising and demonstrating. While demonstrations don’t achieve much apart from having a nuisance value and making headlines, they were unthinkable in Amin’s days. Then, there was no pretence about democracy. Under the NRM the democracy falls back into military regime territory whenever the government feels threatened.

In Amin’s time one would not casually think of stealing public funds or other forms of law breaking to make ends meet. There was almost nothing to steal but also there was a huge possibility of being summarily executed.

Ugandans under Amin uniquely and ironically brought out the good things that happen to a society that is under siege.

In the 70s, unlike today, in many parts there were empty shelves, so it was not an issue of high prices but scarcity. At some points in time, Ugandans were reduced to the rationing of everything from sugar to fuel. In many families sugar became a rare commodity that was only reserved for the little ones. For many the option was humility and resilience. They parked their vehicles and walked to work.

In some instances people decided to pool together resources. One family car in the neighbourhood took most of the children to a particular school and another family would do the return journey. It taught many about the importance of the neighbour. You could not afford to be tribalistic or sectarian.

Because of the disappearance of people which was quite common, you never revealed the location of a neighbour to a stranger.

It is partly responsible for a certain secretive and deceptive streak in many Ugandans. You may never know if they are telling you the truth or what you want to hear and be pleased. You only get to know when they don’t vote for you or sponsor a village drunkard to bad mouth a person at a funeral wake.

Still neighbours looked out for your child so the children learnt to trust and respect elders as protectors and providers. In many cases if one went home and reported the neighbour for spanking them, it would invite another round of kiboko because a parent knew that the neighbour meant well.

In other instances children in a neighborhood gathered together and walked as a group to and from school, with the older children acting as keepers of the young ones. It taught the children about community, sharing, independence, leadership and responsibility.

Families resorted to baking their own bread, chapatti, mandazi etc and sold the surplus to the neighbours and made their own clothes. They grew some cassava, potatoes and tomatoes in the back garden and kept chicken in the garage. In some cases the family car was used as a taxi for the extra shilling, this brought out an entrepreneurial spirit.

In many homes it became untenable to hire a house help or even a shamba boy. The extra stomach to feed and salary to pay could be put to better use. So the children learnt valuable skills in doing house work including cooking, washing cars, clothes and the house.

When many left Uganda from the late 80s to go for kyeyo or blue collar work in the US and Europe they were prepared. A good number prospered by doing multiple jobs because they had learnt to work with their hands at home and did not look at menial jobs as humiliation. The remittances from this work still make a formidable part of the national income.

When the economic blockade was lifted after the fall of Idi Amin, Uganda embarked on economic recovery and gradually people came into the monetized economy and made ‘progress.’ With this came what in many cases is free donor money to pilfer. Many can now afford to own two second hand cars so they do not need to know or be courteous to their next door neighbour who lives on the other side of the wall fence.

As happens when men that grew up in hard times prosper, there is every effort to make sure that their offspring do not go through the ‘challenges’ that made them. So we drive our children not just to school but to expensive international schools for fear that they will be kidnapped, knocked by reckless drivers, be defiled by amorous men or even get too tired to study.

Where their most cherished opportunity of travel outside the home setting was to visit their grandparents in the village for Christmas, now many can fly abroad on a school trip. Travelling on a plane is something which many of the Amin generation children first did in their late 20s or early 30s.

At times we ‘force’ them into all manner of ‘elitist’ hobbies like playing basketball and tennis to bring them into proper society away from television and gadgets. They no longer discover their passion by wandering into the neighborhood and socializing with other children. Many owned at best two pairs of shoes, i.e. canvas for physical education at school and the strong pure leather Bata shoe. At times this valued possession was handed down by an older sibling due to change in foot size. Our children now have entire racks with ‘crocs’, sandals, boots, sneakers etc.

They feel entitled to so many things whose value they do not know or appreciate, that one can lure them into dying for them. These include designer clothes and mobile phones with data to watch Netflix. They are now competing against each other in shows of abundance and opulence.

The cases of depression for those who feel they are falling behind because their parents can’t keep up with the Joneses is astounding.

The day a child asked me why young children were walking to school on their own at 6am instead of being driven, it dawned on me that we have lost the dividend bequeathed to us by the disaster that was Idi Amin’s regime.

Mr Sengoba is a commentator on political and social issues

Twitter: @nsengoba