Prime

Obote, Amin, Museveni and how they were shaped by events

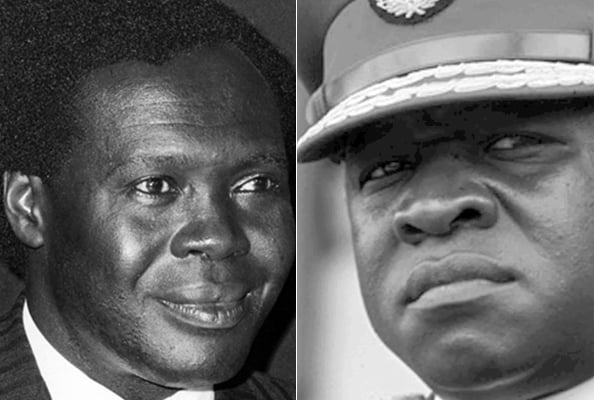

Former presidents Milton Obote (left) and Idi Amin. PHOTOS/ FILE

What you need to know:

- Uganda’s obsession with DR Congo runs through the three major governments since Independence – UPC I, Amin military regime, and NRM. All three, as different as they were from each other, got directly and militarily involved in Congo.

When we think of Ugandan history, most of the focus is on the president. The country is viewed through the lens of the ‘big man’, what he did during his rule and where he took the country.

Almost every newspaper columnist or radio or television talk show panelist today believes the root cause of Uganda’s problems is the politics and the solution is in fixing the politics before anything else.

For many years, I have disagreed with this as I came to study Uganda’s history better and gain insights into the key players and what shaped the decisions they took.

Politics is the response to the society’s religion, norms, expectations, biases, habits, capabilities and interactions.

Contrary to the image we have of leaders as dictators forcing policies and projects onto the country, most of what they do is respond to society.

Whether it is Idi Amin, Godfrey Binaisa or Yoweri Museveni, most of their day-to-day activity is shaped by these national expectations and assumptions.

Milton Obote, Amin, and Museveni were dictators in many ways, but it is just as accurate to say that they were also dictated to by society, the political class, cultural groups and the media.

In the 1960s, the UPC government supported South Africa’s Black anti-apartheid groups.

In the 1970s the Amin government did the same, as did the Museveni government in the early 1990s.

DON'T MISS: What happens post Museveni?

All governments since 1962 have engaged with something called the East African Community and all reckoned with Kenya as the most important neighbour to Uganda.

The fact of Uganda being landlocked and Kenya being the decisive route to the sea has shaped all Ugandan government policy and foreign relations.

Whenever Uganda’s relations with Kenya get strained or Uganda’s access to the sea via Kenya is disrupted, Uganda suffers immensely.

It happened in July 1976 when Kenya closed its border to Uganda, when suddenly fuel vanished from the Ugandan market and President Amin was reduced to symbolically riding a bicycle.

It happened briefly in December 1987 when tensions between Kenya and Uganda led to brief cross-border conflict and a meltdown of Uganda’s economy was averted at the last minute.

It happened again most dramatically in January 2008 at the start of the post-election violence in Kenya, when the price of petrol and diesel quadrupled in just a week, with a litre of petrol in Kampala at Shs10,000 and in the up-country towns at Shs14,000.

Kampala’s usually overcrowded streets were wiped clean of vehicles, such as would be seen on the morning of Christmas Day.

After he became Prime Minister in 1962, the very first country Obote visited was Uganda’s neighbour to the west, DR Congo.

Nearly 24 years later, on January 29, 1986, on the very day of his swearing-in as head of state, Yoweri Museveni flew to Congo, at the time called Zaire, for talks with president Mobutu Sese Seko.

I don’t think Museveni at the time knew or even now knows that Obote’s first foreign trip as prime minister was to DR Congo; something just made Museveni fly to Kinshasa, and yet one would have expected his first foreign trip as president to be to, say, Kenya, which just a month earlier had hosted the Uganda peace talks.

Uganda’s obsession with Congo or Zaire runs through the three major governments since Independence -- UPC I, Amin military, and NRM.

All three, as different as they were from each other, got directly and militarily involved in Congo.

A government official from the mid-1960s if he were woken from the dead today and read about the current UPDF troop deployment in eastern Congo would be left with a feeling of time as being frozen.

All major Ugandan governments since 1962 had to reckon with the Buganda Kingdom.

All three alternatively courted Mengo.

The relationship with Mengo started out warmly and amazingly optimistically with all three and with all three it ended up badly or, at best, one of an agreement to disagree.

UPC entered into the historic alliance with Mengo that secured it the 1962 election victory and Kabaka Edward Muteesa was the best man at Obote’s wedding to Miria Kalule Obote in 1963.

Amin’s first major act as head of state was to facilitate the return of Muteesa’s body from Britain.

President Museveni

Museveni, even before he came to power in 1986, arranged for Buganda’s crown prince Ronald Mutebi to tour the NRA-controlled areas of western Uganda in late 1985.

Another interesting relationship was the one with Rwanda.

Once again, all three major Uganda governments dealt intimately with the Rwanda question, from the governments of the time in Kigali to the thorny issue of the Rwandan Tutsi refugees now integrated in Ugandan society.

The first Obote government welcomed the Tutsi refugees in the early 1960s, the Amin government recruited many of them into the State Research Bureau, Uganda’s secret service of the 1970s, and the NRM government was all but run by them in the first four years after 1986.

A man from Kisoro who was arrested by State Research agents in 1976 for reading Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper, at the time banned in Uganda, was detained at the State Research Centre at Nakasero in Kampala.

Upon his release, he later remarked at how many Tutsi manned the State Research Centre, to the point where the most common language at Nakasero was Kinyarwanda, not the Nubian language, Lugbara or Swahili, as most people would assume.

After that first warm welcome of the Tutsi in the early 1960s, by late 1982 the second Obote government was ordering their expulsion from Ankole.

Amin at some point also had a tense relationship with the Kigali government, and the Museveni government saw the Kigali government close its border with Uganda between 2019 and 2022.

Every head of state has had to reckon with the church, dutifully attending the enthronement of every bishop and attending the Martyrs’ Day celebrations at Namugongo every June 3.

There is no official or legal requirement for Uganda’s head of state to be present at Namugongo, certainly for President Amin who was a Muslim. But even Amin dutifully attended Namugongo.

In fact, it was the Amin government that in 1972 first made June 3 a public holiday in honour of the Uganda martyrs. Before 1972, June 3 was just another day. The Martyrs’ Day event clearly shows how politicians and national leaders must think and act in response to public cultural, religious and social tradition and desires.

These striking similarities in policy across governments, across time, suggests that even in African countries where it tends to be more rule by personality than by policy, there are forces, realities and interests that shape how these leaders act and respond.

Understanding the similarities in policy, troop deployment, and bilateral engagement in the region between the three main governments since the 1960s helps us take a long-term, big picture view of current events.

We start to see beyond Museveni the person and appreciate that he is not the sole hand in Uganda’s affairs.

He, like Obote, Binaisa, Amin and Tito Okello, responds to events, pressure, and interests.