Is the thematic curriculum still relevant?

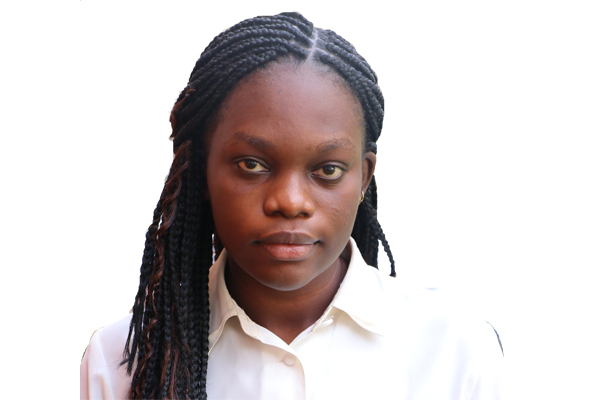

Tiffany Akurut

What you need to know:

- Under thematic curriculum, pupils are taught in their native language in the first three years of primary school. Primary four is the transitional year, as English becomes the primary language of instruction from P.5 onwards.

It is now 16 years since the Government of Uganda introduced the thematic curriculum in our schools. When it was rolled out in 2007, the aim was to make education more accessible and relevant to the learners’ everyday lives.

Under thematic curriculum, pupils are taught in their native language in the first three years of primary school. Primary four is the transitional year, as English becomes the primary language of instruction from P.5 onwards.

Thematic curriculum is premised on the belief that when children start their learning in their first language/mother tongue, they would learn more effectively and efficiently, and also appreciate English language better in their later years.

But Uganda has faced serious challenges. Children not only struggle to learn in their local tongue but also struggle to transition to English. Basic requirements like instruction materials, trained teachers are nowhere.

The multilingual nature of Uganda has also made it difficult to implement the thematic curriculum across the country. This presents a dilemma to teachers on what language to choose when a class is accommodating pupils whose background isn’t the same.

While Uganda’s literacy rates have improved, they have worsened if paired with peers in the region, much to the disappointment of those who thought thematic curriculum would improve literacy. For example, Uganda’s literacy rate increased from 71 percent in 2006 to 73.9 percent in 2021. Conversely, Kenya’s literacy rates increased from 72 percent in 2008 to 78 percent in 2021; Tanzania’s increased from 67 percent in 2010 to 80.3 percent in 2021.

Uganda has moved from having one of the highest literacy rates in the region to one of the lowest. It is therefore difficult to determine whether the thematic curriculum increased literacy rates as intended, its contribution, and what other factors are in play that are affecting the overall quality of education in Uganda. The rural-urban and government-private divide in terms of quality and standards of education has exacerbated the problems that arise because of the thematic curriculum. For example, most schools in urban areas teach in English for all levels due to the multicultural nature of the urban settings. They pass highly in national exams, set in English, as poor rural schools continue to struggle.

Thematic curriculum also uses a one teacher one classroom model, where one teacher is expected to handle all the teaching of one class even for subjects they are not trained to teach. One teacher per class is asking too much and is cumbersome. Also, teachers may not be adequately trained to teach in the widely spoken languages of their regions because they don’t belong to that specific tribe. Teaching in a region that hosts multiple ethnicities, and the language may not have an established orthography, resulting in a lack of materials to teach in that specific language.

Comparatively, in 2017, Tanzania adopted Swahili as the official language of instruction in both primary and secondary schools to improve the quality of education, learner engagement and academic performance. The implementation of this Policy was easier and more successful because most Tanzanians speak Swahili as a first or second language. Uganda has more than 76 local languages without adequately trained teachers and teaching (supplementary) materials for most languages.

It’s about time that we rethought the thematic curriculum. The continued use of the thematic curriculum is likely to result in worsening literacy rates over time.

First, we must acknowledge the multilingual nature of Uganda and therefore think seriously how the thematic curriculum can work in such an environment. After 16 years, it appears rather more ideal to halt the thematic curriculum such that children are trained in the English language right away from Primary One as it was done before.

Second, as Covid-19 revealed, the print and broadcast media in education project saw that all the materials were in English right from Primary One. This meant that those following thematic curriculum were left out.

Third, parents are eager to send their children to school from P1, especially rural parents, in hope of hearing their little ones recite the alphabet in English. Simply put, parents are also uncomfortable with their children going to school and studying in the local language, hence demotivated and the curriculum has never been owned nor embraced outside government.

Ms Tiffany Akurut is an intern at EPRC, Makerere University.