Prime

Why can’t we do right? The rattle of mental corruption

Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- The biggest fuel and driver comes from the top where the rulers have cultivated a belief that one can use public office for private gain without consequences.

Last week, I spent time at Luzira Prison complex visiting a relative. Prison is a leveller. It is the most humbling place.

The Uganda Prisons under its highly competent Commissioner General Johnson Byabashaija, is a markedly different institution today than the one I knew growing up knowing in my ancestral village in Bubulo. Luzira, for one, is very well manned and the officers you encounter are professional and friendly. But that is not all. More on this in a moment.

Prison is a tough place. Regardless of one’s wealth and status, it is the place you get to be just like the next person. With increased threats and the need to undertake precautionary measures, Luzira has become far more fortified.

Between last April when I last visited and last week, the layers of security and scrutiny had grown. And compared to 10 years ago, it is a wholly different world. I first went to Murchison Bay section back in 2011. It was easy and convenient. I sat on the inmate’s bed and we chatted.

This time, in addition to four layers of vetting and red tape, you only get to speak to the inmate in a caged and crowed room with the conversation happening through small outlets of iron bars.

The noise from the many other people speaking to their loved ones make it impossible to have a meaningful conversation with the inmate you are seeing. But it is the very best you get. Such is the extent to which incarceration is taken.

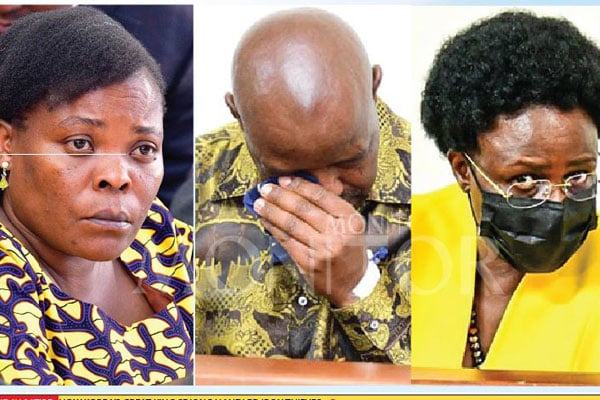

At the second last waiting area before one gets to the inmate, the inmate’s name is announced to the waiting crowd out there so the visitor(s) concerned comes forward. As I waited for my person’s name to be shouted, the one that came first was that of Mr David Chandi Jamwa! It was a most sad moment.

Yes, David Jamwa, the incredibly brilliant former managing director of the National Social Security Fund, is still serving prison time in Luzira. Knowing how obscenely corrupt the current Uganda rulers are, the fact that Jamwa is in prison on corruption charges is testament to the tragedy of dear country. But that is a story for another day.

I argued last week that we are a society conditioned to do wrong. We now have a convoluted system where doing right is punishable. By far the most pervasive belief and practice now is that when doing your job and providing a service, whether in a government position or private job, you use whatever power you wield to extract rents from members of the public.

Nowhere do you go in Uganda today and you don’t have to deal with officials and hangers-on lining up to solicit a bribe or some kind of financial extraction so as to get a service. Even at Luzira Prison, as noted above, with its professionalism, you encounter uniformed prison staff unabashedly seeking to extract money.

The lady or gentleman registering you at the last security screening will foot-drag and dillydally in ways that signals to you that reaching for your wallet will make matters quicker and easier. To be sure, the prisons staff is despicably underpaid, much like the police officer and many other government employees.

But poor pay cannot be the basis for inefficiency and failure to do one’s work except when handed an inducement. Quite to the contrary, the best way to earn sympathy and an unofficial financial reward from members of the public is to exhibit professionalism and good conduct at your job, thereby compelling someone to reach for their wallet in appreciation. Elsewhere, it is called tipping! It comes as a reward for good service.

What we have in Uganda is increasingly the kleptocratic system of the Mobutu rulership in the Congo. There is a high temptation and default state of mind to extort in the absence of official salaries.

But Mobutu’s system had declined so drastically that the only way to earn a living was to extract. Ours in Uganda today is slightly different. Salaries are paltry but they are paid, often on time. The crux of the matter is the mental programming that extracting a bribe or kickback is a normal act and that not seeking and getting one is against the ‘norm.’ This has become part of the national psyche that I wrote about last week.

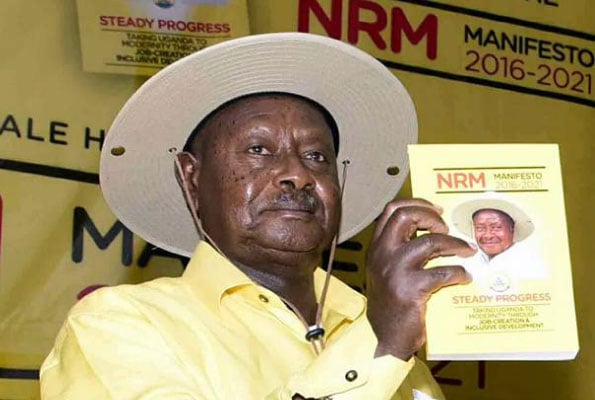

The biggest fuel and driver comes from the top where the rulers have cultivated a belief that one can use public office for private gain without consequences. This problem has grown in leaps despite growth and proliferation of anti-corruption agencies, including a separate court division devoted to corruption.

The incarceration of Jamwa, whatever his wrongs and the merits of his case, is itself indicative of a corrupted system. The bigger societal problem is that we are now a country whose programming and state of mind is steeped in corruption.