Prime

Museveni rejection of Amin institute and implications for Uganda’s future

Former Ugandan President Idi Amin

What you need to know:

- A primary school drop-out who seizes power and rules the way he did for eight years makes Amin an enigma and legitimate subject of intellectual/academic study. It’s not something to be wished away or forgotten as the President proclaims.

I have keenly followed discussions on contents of President Museveni’s letter which he authored on October 5, 2023, but was made public only on Saturday.

The President addressed the 2-page letter to Education Minister Janet Kataha, who is his wife, and in it he details reasons for rejecting a proposal to establish an Idi Amin Institute.

Proponents of the Institute galvanise individuals seeking a holistic examination of the person and government of Idi Amin Dada who ruled Uganda from January 25, 1971 to April 11, 1979 when a combined force of Ugandan dissidents supported by Tanzania toppled him.

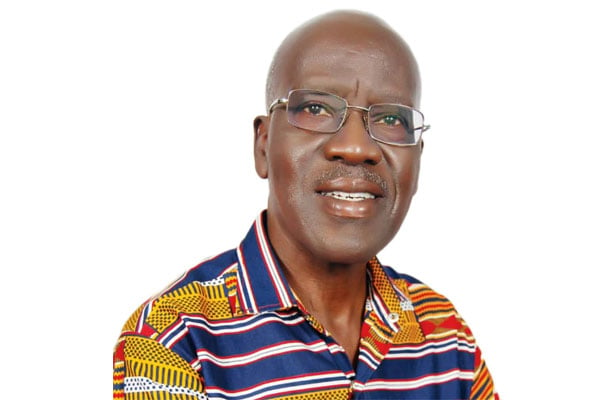

The Spokesperson of the group, which attempted to organise an Amin Memorial Lecture but were rebuffed by Muni University, the intended host, is Mr Hassan Kaps Fungaro, a former Member of Parliament for Obongi and current National Mobilisation Secretary for the opposition Forum for Democratic Change party.

President Museveni copied his three-point letter to Mr Fungaro who had written to the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE), seeking licensing of the Amin Institute. It’s unclear how or why the NCHE, which has the legal mandate to set parameters for establishment of higher education institutions and approve the curriculum, elected to transmit the determination of the fate the proposed Amin Institute to President Museveni.

My assumption is that the Council second-guessed itself and reached to the President in order to clothe itself, considering the political sensitivity related to Amin whose dead the President previously said he would not even touch “with a long stick”.

Thus, Mr Museveni’s rejection letter of this month is a continuation, not a start, of his disapproval of a man who has been in the grave, on a foreign soil in Saudi Arabia, for now 20 years.

I’m injecting myself in the conversation because the scrutiny of the content of Mr Museveni’s letter and his rejection decision on the planned Amin Institute is being framed as a postmortem - an examination as to historical problems giving rise to a fact.

Yet, the President’s proclamations potentially affect the fate and fortunes of persons identified individually or collectively as Amin’s people.

A deconstruction of the euphemism “Amin’s people” yields West Nilers, natives of the region Amin hailed from; people who worked with or under Amin, which President Museveni in his letter appears to christen as “colleagues of Idi Amin”; and, anyone who supported or at present speaks anything good about Amin.

A fourth column, who might be in indirect reference, would be those who fear being exposed if Amin era commissions and omissions are examined impartially and in detail. So, their motivation would primarily be a cover-up in which Amin is the sand dune who, when removed from the political equation, will lead the political flash flood waters into their living room and twilights of their lives/careers.

This explains the appeal to some of the demonisation of Amin for alleged excesses of his government, more so through executive officialdom, which has in turn ordained a linear thought - that Amin was evil. Full stop! Any contrarian or positive mention of Amin or his deeds, by that thought, is presumed revisionist, unacceptable and approving of his ills. It’s likened to white-washing.

This is problematic for it fashions a binary people and world - of good versus evil - yet the acts of Amin, like that of Museveni or any other leader should be examined from all sides for no man or woman has only one side. Why then foreclose discussion relating Amin’s good side when the talk about his bad is unrestricted?

The bandwagoning appears intended to achieve one thing: erasure. The President calls it in his October 5 letter as the “history to be forgotten”.

Who in the history is being forgotten and why? It’s Amin’s people I alluded to earlier; West Nilers, ex-officials of Amin’s government and anyone likely to speak good of him, and those seeking to cover their complicity. Why? Because they were, or are, so evil —- and any thought or association with them is inherently dangerous.

Simply put, according to the President’s logic, if you fall in any of the three categories, you should be shunned and “forgotten” because you are a postmortem - a problem.

That label disadvantages those in the fold because it reduces an examination of their worth, or the lack thereof, through singularly the glass prism of Aminism. The implication of this social engineering, of a bad people, is deleterious because it replicates by word of mouth and evolves to the philosophy of “othering”.

It then erodes the esteem of such people, who begin to doubt themselves and seek affirmation from others. Further, negative label validates vilification (and erasure) of a people and their contributions, renders them effeminate and unquestioning, reducing them to accept any positives assigned to them as either favour/privilege, even where and when it’s a right, or luck, even when deserved.

In extreme cases, it justifies the elimination altogether of such devalued people for they add nothing positive, except trouble, to society for their presumed inherent evil nature. Put another way, society is better without them, which undergirds the case for them to be forgotten.

Otherwise, a critical analysis of the President’s letter, based on its content, leaves it legless. Firstly, he writes that Amin’s government was illegal and had no right to impose itself on Ugandans. Reason? Amin seized power in a coup on January 25, 1971. Similarly, Museveni barelled his way to power on January 25, 1986 (official reference is January 26) after a five-year guerrilla war. How then can it be that Mr Museveni is accusing Amin when both took power through the power of the gun, and not the ballot?

Former Obongi County MP, Mr Hassan Kaps Fungaro, and Mr Habib Asega, address the media in Arua City on August 22 about plans to launch an Idi Amin memorial lecture at Muni University. The university later denied having knowledge about the lecture, which was slated for September 1. PHOTO/FILE

In short, both men at different times on similar days imposed themselves on the country and Ugandans. How many people died in Amin’s coup? How many died during the five years of National Resistance Army/Movement war that Mr Museveni led? The answers to these questions lead to my engagement with Mr Museveni’s second point in the letter, which is that Amin, which I assume meant Amin’s government, killed many Ugandans including national luminaries.

The number of Ugandans killed allegedly on the direct orders of Amin, or during his reign in state-inspired violence, remains unclear and contested. Ugandans missed an opportunity for justice when governments that came after Amin failed to seek his extradition from Saudi Arabia to face trial so that there would today have been a verdict by a court of law for his culpability in the crimes as widely documented and spoken about. I have been intrigued why this was the case.

This is because Ugandans who have lost loved ones in the hands of state actors under Mr Museveni’s government may rightly blame him, yet in reality Mr Museveni’s may have nothing to do with a soldier or armed State operative who shoots and kills or maims a citizen.

Other than killings in the Luweero Triangle, which protagonists in that war blamed on each other, other easier-to-reference incidents include that of Mukura, killings during the 2009 Buganda riots, the Walk-to-Work demonstrations in 2011, the bombardment of the Rwenzururu Kingdom palace and, in 2018, the shooting dead by security forces, by President Museveni’s admission, of 54 Ugandans on Kampala streets in broad day.

The pain caused to families of these victims is similar to the undiluted grief of families whose members or relatives were killed during Amin’s government, or simply disappeared the way Opposition is claiming of the fate of some of their supporters today.

It’s why I agree with the seemingly wild push by Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister Norbert Mao, and before him other elders and luminaries, that this country thirsts for truth-telling, reconciliation and healing to move forward as a unit.

Is an Amin Institute, therefore, the answer? Likely not. But an Institute would advance studies that can confirm or confute claims, leading to establishment of new knowledge. To paraphrase Prof Akiiki Mujaju, every political party, a people and government has a womb of violence (by birth).

Elsewhere where the evil of man against man and woman against woman has occured, there are things like the Holocaust Memorial Museum in the US, Genocide Memorial Museum in Rwanda, Apartheid Museum in South Africa etc. The ideation is to create historical factual repository as a living reminder on the path that a country or its people should reject in order to eschew apocalyptic outcomes. In addition, it’s cash cow from paying tourists.

In the contexts above, I’d even proposition establishment of an Idi Amin Museum, which could operate under the purview of such an Institute or purely private or public-private partnership. And neither the museum nor an institute would serve to valorise Amin. It would meet demands, current and future, of accuracy and reference.

A primary school drop-out who seizes power and rules the way he did for eight years makes Amin an enigma and legitimate subject of intellectual/academic study. It’s not something to be wished away or forgotten as the President proclaims.

Similarly, I’d also propose the establishment of a Museveni Institute for Peace and Security Studies for his doyen role on regional security and politics.

Now let me briefly turn to the third and last point that Mr Museveni raises in his October 5 letter: that Amin destroyed the economy by expelling the Asians. Amin’s explanation was that transfer of political power was no independence unless and until Ugandans gained economic independence and controlled the making and ownership of the country’s wealth.

As a socialist-turned-liberalist, Mr Museveni espouses the idea of wealth creation regardless of the economic player or control. Both are gambles to economic prosperity, which is why the verdict on each is debatable. Amin’s approach, the false starts notwithstanding, created indigenous entrepreneurs. Mr Museveni’s policy, the fissures notwithstanding, has increased the Gross Domestic Product of Uganda multiple-fold since 1986.

In the final analysis, the three points Mr Museveni raises about Amin are in essence about himself and the living (the four types of Amin’s people I hazarded) than the dead leader.

In conclusion, President Museveni, like Amin, seized power by force and imposed himself on Ugandans, although he after 10 years allowed elections, which Amin didn’t during his 8-year rule. Ugandans have died in the hands of State actors under Mr Museveni’s now 37-year government as they did under Amin, although there is no accuracy on the numbers and fear forestalls candid discourses. Lastly, by rejecting the idea of an Amin Institute, President Museveni sketches the portrait that a future leader of Uganda, who considers his era better “forgotten”, could potentially use to erase all that Mr Museveni and others he has served with, have done for the country.

The author is an alumnus of both the British Government’s Chevening Scholarship and US Government’s Fulbright (Hubert H. Humphrey) fellowship and presently the managing editor of Nation Media Group-Uganda. The views canvassed in this article are his own.

Museveni's take

President Museveni writes to First Lady and Education Minister, Ms Janet K. Museveni about Amin institute proposal

October 05, 2023

STATE HOUSE, ENTEBBE: I have seen the letter from Dr. Kagume of the National Council for Higher Education inquiring about Hon. Fungaroo’s request to start Idi Amin Institute. This is a wrong request and it should be rejected.

First of all, Idi Amin’s Government was clearly illegal. It had no right to install itself over our country. Why? By 1962, Uganda had a Constitution under which we had the election of 1961 and 1962.That Constitution was altered in 1966/67 by a Parliament that had been elected in 1962.Were their actions constitutions? That needs to be debated. However, Amin was clearly unconstitutional.

Apart from his unconstitutionality, he committed a lot of crimes-the killing of the Acholi and Lango soldiers in Mbarara, the killing of the prisoners in Mutukula Prison, the killing of Ben Kiwanuka, Basil Bantaringaya and his wife and so many other killings. All these are well-known and were documented by the Judicial Commission of Inquiry headed by Justice Oder.

We do not have to talk about Amin destroying the Ugandan economy by his ignorant expulsion of our Indian entrepreneurs that went away to enrich Canada and the United Kingdom.

Therefore, it is not acceptable to license an Institute to promote or study the work of Idi Amin. It is enough that the forgiving Ugandans forgave the surviving colleagues of Idi Amin. Let that history be forgotten.

President Idi Amin with some of his Cabinet ministers in a meeting during the 1970s. After seizing power in 1971, Amin named appointed 18 Cabinet ministers. The Cabinet did not have a woman and had only him and Lt Col Obitre-Gama as military officers. PHOTO/FILE

About Idi Amin

In 1925, General Idi Amin was

born in present day Koboko District .

He was raised by his mother, a traditional herbalist, and her family in a Roman Catholic household until he decided to convert to Islam and attend an Islamic school.

In 1946, he joined the British colonial military regiment, the King’s African Rifles, and quickly rose from an entry-level position as a cook to the highest position that could be held by a black African in the British army, a warrant officer.

In 1961, he became one of the first two black commissioned officers in the regiment when he was promoted to lieutenant.

He came to power in 1971 after overthrowing Milton Obote’s government and declared himself President of Uganda. He cited 18 reasons, such as unwarranted detention without trial, widespread corruption, State of Emergency, high taxes, creation of divisions in the army and the society, a plan to develop Lango at the expense of other parts of Uganda, to seize power.

He made the move when Obote was attending a Commonwealth summit meeting in Singapore.

When he took over power, he was quoted in ‘‘Uganda, the Human Rights Situation’’ by the US Senate, saying : ‘‘My mission is to lead the country out of a bad situation of corruption, depression, and slavery. After I rid the country if these vices, I will then organise and supervise a general election of a genuinely democratic civilian government.’’

However, by 1978, Amin’s regime had fallen out with the West and leaders in the region led by Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. Nyerere mobilised the Tanzania Peoples Defence Force to support Ugandan exiles under the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) in ousting Amin. On April 11, 1979, Amin fled to Libya after Entebbe and Kampala were captured by UNLA with support from the Tanzanian forces.

Amin later moved to Saudi Arabia, where he lived until his death on August 16, 2003. He was buried in Saudi Arabia.

However, a month before his demise, one of his wives, Madina, pleaded with Mr Museveni to allow Amin return to Uganda. But the latter said Amin would have to ‘‘answer for his sins the moment he was brought back’’.

The author is an alumnus of both the British Government’s Chevening Scholarship and US Government’s Fulbright (Hubert H. Humphrey) fellowship and presently the managing editor of Nation Media Group-Uganda. The views canvassed in this article are his own.