Prime

My Ebola Story: The life of an Ebola ward cleaner

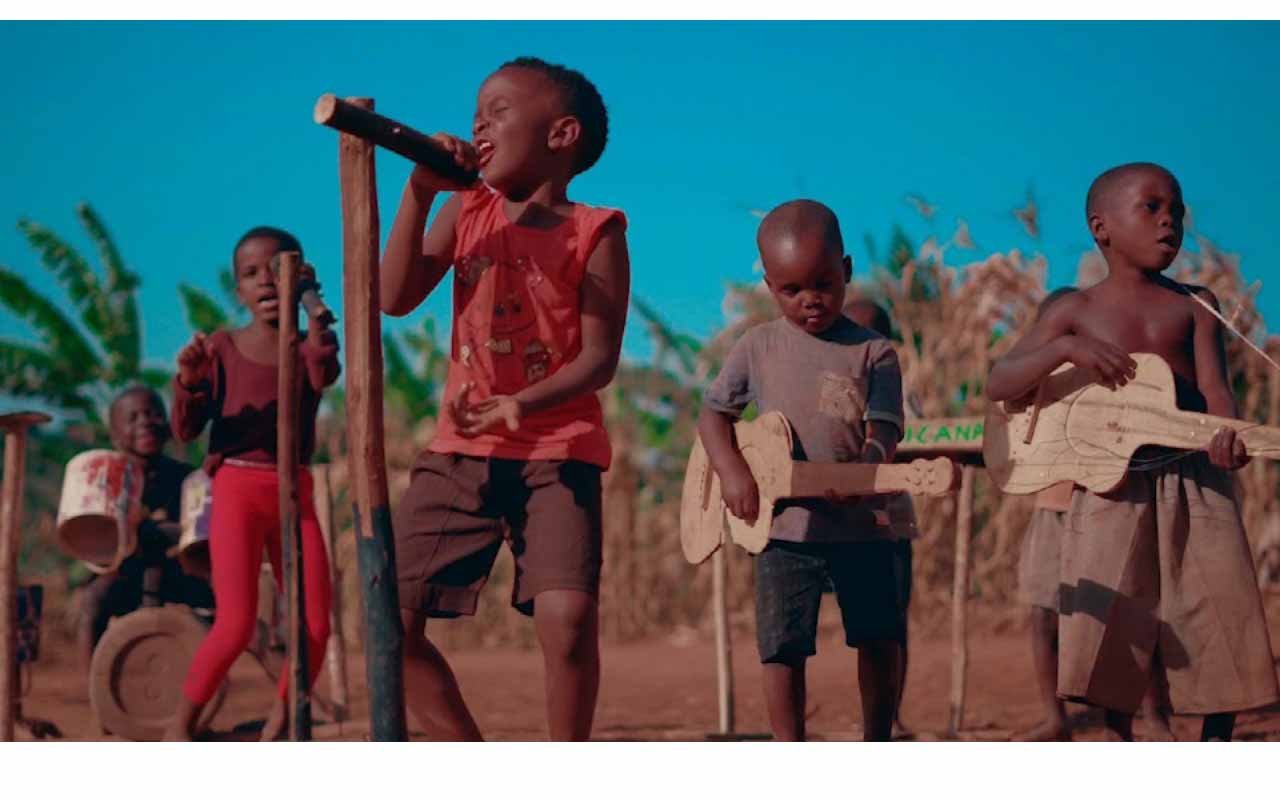

Francis Ssempijja. Photo/Barbra Nalweyiso

What you need to know:

- On January 11, the country declared an end to an Ebola virus outbreak that had emerged almost four months earlier and claimed the lives of 55 people. In this 14th instalment of our series, Francis Ssempijja shares his experience as a hygienist in an Ebola treatment centre.

When the number of Ebola cases rose in October and the Ebola treatment unit at Mubende Regional Referral Hospital got full, the Ministry of Health made a proposal to set up a new treatment centre which would accommodate a big number of patients. The new centre would be at Kaweeri. Doctors were deployed to Mubende and vacancies for various positions were advertised through the district service commission.

Among the applicants for the jobs was Francis Ssempijja, a 32-year-old resident of Nkanaga in Mubende Municipality. He looked at this as an opportunity to earn money since his financial status was not good due to the lockdown that had been imposed on the district. He also had his pregnant wife to think about.

“I am a painter. When our boss saw that there was a lockdown and cases were on the rise, he decided to suspend all the work thinking that we might infect each other, since everyone was coming from a different place. I remained with no job yet I had a wife who was seven months pregnant and needed much care,” he said.

At the time, Ssempijja was volunteering at the Uganda Red Cross Society (URCS) where he was trained in safe and dignified burial (SDB) management. While at URCS, he carried out burials for two people. It is here that he heard about Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) advertising jobs for hygienists to work in the new Kaweeri Ebola treatment centre.

“I went and applied for the job because I realised my wife wasn’t comfortable with the kind of work I was doing at URCS of burying dead bodies. She fears dead bodies a lot so whenever I came back home, she would feel nervous yet she was in a sensitive condition. I might have lost my family if I insisted on working for Red Cross,” he says.

He did the interviews, passed and started working on October 26.

“We were all working as hygienists but it consisted of doing different things including cleaning outside, where the doctors work from, the changing area and their resting corner, washing the clothes they [hygienists and doctors] used to wear, washing the scrubs and boots, transporting oxygen from the oxygen plant to the treatment wards, cleaning the toilets, mixing chlorine used for washing and disinfection and other kinds of work. However the rosters were changed every after two weeks,” he narrates.

Ssempijja says he was majorly an internal hygienist following the doctors’ request to be one of the eight people who would work inside the treatment wards because he was friendly and easy-going.

He adds that many of the patients were scared. They were working with a psychosocial team but in many cases, the team always was scared of entering the rooms to speak to the patients. So sometimes the hygienists found themselves having to do their work of speaking and providing counsel to the sick.

Ssempijja recalls one of the times when he thought that he had contracted the disease. Sometimes when the hygienists went to clean the ward, patients would ask them for help since they were not allowed to have caretakers. The patients would ask for a bucket to vomit in. Once, as Ssempijja was trying to get the bucket to a patient, they accidentally vomited on him.

He got scared thinking that he was infected.

“The patients would apologise but we understood. To work inside the treatment wards, you had to have a big caring heart and be understanding, depending on the condition of the patients; they didn’t need people shouting at them,” he says.

“That situation wasn’t easy to adapt to. Even when the patient vomits on you, you have nothing to do other than giving that patient counselling. The patient would feel that he/she has done something wrong and feel awful because of his/her actions so it was our responsibility to calm them down and get out of the room to go and change,” he adds.

And sometimes as soon as they had changed into fresh coveralls, they would be called into another ward with a patient in critical condition who has vomited blood, which they had to clean up.

“Living in such a situation was so scary and very hard to adapt to. What surprised me was that I didn’t fear the dead bodies. It was the vomit, blood, diarrhoea and urine which was scary as we were told that those were so deadly if you get in contact with them. You would get scared wondering if maybe your glove had got a hole in it and the waste passed through,” Ssempijja says.

“However, at a certain point, we adjusted to this because the psychosocial team was there to give us support through counselling. Sometimes, I would counsel colleagues who were scared,” he adds.

He says his worst moment was when a military veteran from Kibalinga died. The two had become friends and the veteran called him his son.

“We used to talk because I was among the people who received him from the ambulance and took him to the ward where he had to receive treatment. I asked to call him Kazeeyi since he was old,” he says.

“Kazeeyi had become my friend for the three days he spent in the ward but what still hurts and scares me is the day he passed on. He was on oxygen but he could talk. He told me that he couldn’t breathe properly; at that time the oxygen was over from the cylinder,” Ssempijja recalls.

“I made an alert for us to get more oxygen cylinders. The minute the cylinder arrived in the ward, Kazeeyi held my hand tightly. He threw his legs and other arm in the air. I tried to bring him back, but he was so strong. He died while holding my hand and staring at me. The pain he went through as he was dying touched my heart and up to today, I still see him in my dreams,” Ssempijja recounts.

After the old man died, Ssempijja was asked to work on his body but he couldn’t. He walked out of the room crying. He almost collapsed in the ward because he couldn’t feel his legs; he was helped and carried out.

“It took me time before I could enter the treatment wards. I told my bosses that what had happened scared me,” he recalls.

Ssempijja adds that a few days later, he was assigned to handle a body in a different ward, however, he was still dealing with the trauma of Kazeeyi’s death and was unable to do the task.

One of his bosses ended up handling the body.

He says the memory of Kazeeyi lying on his bed lingers in his mind. The psychosocial team offered him support and eventually, he returned to work. It, however, took a long time for him to deal with the trauma.

Ssempijja also recounts a moment when a patient named Gloria kept pleading with them to help her to end her life because of the difficulties she was going through.

“Gloria had reached a time when she wanted to take an overdose of medicine to end her life because of the situation and life challenges she was going through. She was vomiting blood every five minutes. We did not think she would survive but after she shared her problems with us and through my counselling, she listened and is still alive,” he says, clearly one of the moments he is proud of.

There were other challenges Ssempijja got while working at the treatment unit, including getting nightmares. Another challenge was carrying patients. Some patients were heavy and yet he and three others were the only people who could carry the sick from the ambulance onto a stretcher and into the ward.

He recalls a scenario when a patient tore his coverall as they were carrying her from an ambulance to a stretcher. He told his colleagues to put her down and immediately made an alert for the team to send someone else since he couldn’t enter the room while exposed.

“I got scared thinking this time I had contracted the disease. Even when I went to change, I felt like I already had Ebola and the following day I felt sick. Maybe it was just the fear I had got thinking I had been infected,” he says.

Optimistic

Despite the challenges Francis Ssempijja, a former hygienist at the Kaweeri Ebola Treatment Centre, went through while working at the centre, he does not regret doing the job because of the experience he got. He knows that should the country get another outbreak, he will be able to serve well, having got experience.

Ssempijja also says although he got money to cater for his family, it is his father’s humanity, serving the community as a part of a Village Health Team that won him over. That’s why he also became a VHT and helping the community or a person is his pride.