Prime

My journey to the loving arms of a king

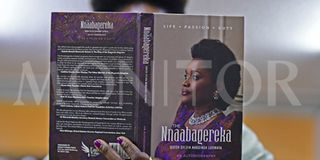

A woman reads a copy of The Nnaabagereka book. Photo | Abubaker Lubowa

What you need to know:

- In the first part of this series, Once upon a Queen: Nnaabagereka’s story, Sylvia Nagginda Luswata describes her early life before becoming the Queen of Buganda.

Crib baby

Mum, Rebecca Nakintu Musoke, had come to England to study nursing on a scholarship. As fate would dictate, she reconnected with a handsome young man she had met in Uganda, named John Mulumba Luswata, at Northern Polytechnic (presently University of North London). Like her, John was a student on scholarship.

John had taken a liking to mum. Naturally, his attentions were much too flattering for a young girl, living so far away from her home, so she fell for him. The two started hanging out and travelling away on short breaks to the English countryside.

When mum became pregnant, all hell broke loose. Having a child out of wedlock was scorned upon in that small conservative English town of Shakespeare Village.

“When I found out that I was pregnant, I was terrified,” mother recalled later. “The Ugandan embassy had standing orders from our government to return unwed pregnant students back to Uganda, so I couldn’t let anyone know about it, I was mad at John, mad at me, and mad at everyone.’ Needless to say, my sponsor was devastated. She moved me into a young mothers’ shelter and found a social worker to walk me through the next few months. The shelter was comfortable, but I was extremely isolated, I was the only black girl there.”

Mom was forced out of school for the remaining five months of her pregnancy for fear of what they called ‘negative influence’ on the other girls. The shelter provided full prenatal care until delivery. Then; policy was to immediately place the new-born child into foster care to prevent the young mother from attaching to the baby.

When the time had come, she was admitted to Leamington Spa Hospital. It is on that winter afternoon of November 9, 1962, that I was born to my frightened mother in the small town of Warwickshire, United Kingdom.

The nurse placed me in my mother’s arms. She was very happy. She said she couldn’t get her eyes off of me. Some of the other mothers said that they had never seen a black baby before. Remember this was in the early sixties.

Visitors were walking in and out of our ward. Some stopped by to say hello, but none had come to see Mom. She was afraid and lonely. Aside from her social worker, it seemed as though no one really cared about her or even knew her.

Two days later, Mum’s social worker came to discharge her. We were taken back to the shelter where we would stay until a more permanent home was found for me.

Mum said: “I didn’t know how to take care of her. I remember this one evening, Sylvia had been crying for hours, I couldn’t console her, so I decided to just lay her next to me. We both drifted off to sleep. Next thing I hear is my panicked nurse. She couldn’t find Sylvia. We looked around, but no one knew where my baby was. Out of desperate resignation, I thought to look under the bed, and there she was. Somehow, she had rolled off the bed on to the floor, and under the bed. Thankfully, she was fine.”

They found a foster home, and for four and a half months, a generous English family provided excellent care for me.

Mother recalled: “One thing I remember is they had problems combing her black hair. She had a sensitive scalp, so every time they tried, she yowled with pain. They decided to wait for me to do it whenever I visited. Unfortunately, Sylvia started to associate my visits with pain, so she hated my visits, I wished I could take care of her. I wished I could send her to my mother, but she was unwell. She had also just given birth to a newborn, my sister Milly.”

My grandfather, Nelson Sebugwawo, was visiting London on government business. He was eager to see his son’s child, but had not been able to. When he asked to see Mum, she had an interesting proposition for him. Since she and John were still in school, she suggested that he, Jajja Nelson, should consider taking me back with him and raise me instead of the British foster care system. He heartily agreed.

As dad recalled: “Given our circumstances, we couldn’t take care of her. We looked at adoption but decided instead to send her back to Uganda. My mother and father would take care of her until we were done with school. Giving my daughter away like this was one of the hardest decisions I had to make.”

Finally, the day had arrived. My grandfather couldn’t fly back to London to pick up this five-month-old baby, so a lovely lady, Nurse Carruthers, offered to fly me back with her to Entebbe in Uganda.

On that warm February afternoon of 1963, I was handed to my grandparents to be raised, in the safety, ways, and traditions of my people.

Kabaka Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II and Nnaabagereka Sylvia Nagginda on their wedding day. Photo | File

My aunt Kolya Ekiriya recalled: “Initially, they told us that we wouldn’t see her until she was old enough to travel. But then suddenly, they said she was being brought home. So, we all went to Nkumba to welcome her. At around 2pm, the car arrived with this tiny baby in a crib. She was so cute. We didn’t want to leave.”

They gave me a nickname mwana wa mu kibaya meaning, ‘crib baby’.

My grandparents became father and mother to me. I called them Taata and Maama meaning father and mother. They were all I knew and all I had. Their children, who were technically my uncles and aunties, were my big brothers and sisters.

Taata’s house was warm and full of life. Built in 1914, he had inherited it from his own father, my great grandfather, Saulo Sebugwawo. Taata had twenty-eight children: thirteen from his first wife, my grandmother Jajja Catherine Namayaza Sebugwawo (Maama), 10 from the second wife, Jajja Robinah Naluwoza Sebugwawo, and five others. Although we didn’t all live in the same house, yes...ours was a full house most of the time. “God has blessed me with a large family,” Taata would say, “and along with it, the ability to provide for them.”

Taata had the biggest heart. There was always plenty of food to eat and milk to drink. We were really blessed with abundance; I still remember the huge evening meals. He and some of the grown-ups would sit up at the dining table, while we, the kids and Maama, sat on floor mats right next to them.

Meals were a communal affair. We all had to eat at the same time and the same food-—whatever was cooked for the day is what we all shared, no exceptions. You couldn’t be picky with the menu or preparations.

My grandfather (Taata) named me Nagginda, a name from his clan, the Musu (Cane Rat) Clan which I am part of and is one of the 52 clans of Buganda.

First glimpse at the prince

Taata was a fun person. He liked exposing us to different forms of entertainment and learning. He would take us to the game parks, to plays and music shows, and the children’s circus. He would take the boys to see football games and boxing matches. He would also take us to traditional events, like when I was about 9 years old in 1971. It was one of the events that was organised for then Prince Ronald Mutebi upon his return home from the UK for the official burial of his father, the late Ssekabaka Mutesa II.

ALSO READ: Buganda mourns Nagginda's father

I remember the venue, a place called Kakeeka, near the golf course in Entebbe. There was a church nearby. I remember the big crowd and the jubilation when we saw the Crown Prince. His father, Kabaka Mutesa, had passed away only two years before.

Memories of the fallen king and the abolished Kingdom were still very fresh. Seeing the prince gave hope to many that maybe someday, the Buganda Kingdom could be restored. As the young prince sat on the raised platform in front of the crowd, people were ecstatic. The sound of kiganda music and drums permeated Entebbe town as orators and speakers praised and encouraged the young prince.

I don’t remember what was said or much else about the auspicious occasion. At nine years of age, I was one of those kids who didn’t make much of jubilations or the musings of adulthood. None of my age-mates really understood the fuss at the time. I still remember the grown-ups being so excited. My other relatives and I sneaked out of the main grounds to play our own games, running around and drinking soda from bottles.

Oh and we had no openers. We used teeth, and guess who was designated bottle opener? Yours truly! I distinctly remember running around with a bottle of Fanta in my hands and stopping to stare at the prince seated in front of the crowd, before taking off to return to play. Little did I know that 28 years later, he’d be my husband.

School influences

‘Kati ogenda Gayaza, announced Taata, which means, ‘Well, now you will be going to Gayaza’.

With those chilling words, my world would once again be turned upside down, and consequently, the trajectory of my life would forever be impacted. I had just completed primary four at Lake Victoria School.

No one explained why I was being transferred. And no one cared to respond to my quizzical stares. And so the following term, I was enrolled in Gayaza Primary School.

Overall, I know I would not be the woman, mother, wife and leader I am without that critical developmental time in Gayaza Primary School.

Needless to say, life in boarding school was hard – perhaps too hard. We had a militaristic disciplinary culture, which the administration honestly believed helped make Gayaza Primary School the envy of any girl’s school in East Africa. That said, I think that the potential scarring of some kids with certain personality types does not justify the no-doubt enormous academic benefits from these kinds of educational models. I believe that early enrolment into any boarding school removes kids from needed critical parental bonding which can potentially set them up for relationship dysfunction in adulthood.

However, I do believe that kids who are too sheltered, or kids who are not given the opportunity to develop social skills outside of their home environments also tend to exhibit dysfunctional relationship behaviour.

So I say to parents who are reading this, love your kids, protect them, nurture them, grow them, educate them, but be ready to let them go and discover who they are. Indeed, they will always need your guidance; but more importantly, they will need to figure out their world. Is this easy? Of course not. To any loving mother, your child will always be your child, even when they’re much older.

This is how my story started

On August 27, 1999, I became the Nnaabagereka of Buganda. Me, a simple girl, had fallen in love with a king and become his wife—the queen in one of Africa’s great civilisations, the Buganda Kingdom! I was extremely grateful for the opportunity to serve a special people who had thrived for more than 800 years.

As I basked in the warmth of this indescribable honour, reality quickly set in; my life as an ordinary girl had ceased. I had stepped into a large, undefined role, I assumed colossal responsibilities for the people of Buganda, and along with that, their high expectations. I had to be the Nnaabagereka from the moment I said my vows to marry their Kabaka.

Young Sylvia with grandfather Sebugwawo and Ssenga (aunty) Cate Bamundanga.

I was a normal girl, but henceforth, no more. You see, our subjects fully expected me to act like royalty. Yes...I had to do and say the right things 100 percent of the time. There was absolutely no room for mistakes. I felt like I was almost set up to fail them, especially since I had no such grooming.

I grappled with the cultural definitions of my role. Who exactly is the Nnaabagereka? What was expected of me? There was no defined role for Nnaabagereka other than vague generalisations such as, ‘You are the wife of the Kabaka, and you exist to support him, go to functions with him, bear his children, and be his wife’!

Not bad, I thought, I can handle that! But was that all?

New chapter

Thankfully, I quickly found my bearings. After 18 years in the United States, this was the beginning of a new chapter in my life: an exciting chapter that challenges conventional wisdom on how change can happen in the 21st century. As Nnaabagereka, I was placed close to the apex of a traditional cultural value system in a modern world and, above all, to grow as a leader, while setting the pace for fellow African women leaders.

The title Nnaabagereka is derived from the Luganda word okugereka that means ‘to prepare and apportion’ and ‘to serve’. I had two distinct choices: I) maintain the status quo, be the traditional wife and stay safe; or 2) play an active role in shaping our community and our beloved nation. I chose to do both. This is my story.