Prime

Training autistic children to fit into society

Komo and his mother. Photo by Godfrey Lugaaju

What you need to know:

- Christine Kaleeba says her son has to be guided most of the times especially for activities out of his routine. Outings such as shopping, travelling are guided.

- Kaleeba adds that Komo does certain things out of routine and the need to have a clean environment.

At two, her son was making no developmental progression. He could not speak a single word, was very aggressive and took no interest in children his age. He was happy playing on his own.

Elizabeth Najjemba Kaleeba, a social worker, lived in Geneva at the time. At that time (2000), she says autism attracted a lot of debate in Europe which gave her a chance to read widely about it and the more she read, the more she realised that most of the information especially symptoms applied to her son.

“His grandmother had been very keen on his milestones and was one of the first people to point out that he might have autism. In a routine check-up for milestones achieved by most two-year-olds in Geneva, a diagnosis was made.

Komo being her first born child, the mother of four was overwhelmed by fear and uncertainty at the autism diagnosis.

“However, with support from family and friends and counselling, I started believing he would one day be able to communicate his feelings. I still have hope although I should say I am more resigned to him being like this most of his life.”

While in Geneva, it was easy for Kaleeba because she lived in a society which was aware about autism and the level of acceptance was also very high. “I came back to Uganda when he was three years and at that time, I was already firmly grounded in accepting my son’s condition. Of course some embarrassing situations occurred but as he grew older, he became more tolerant of his surroundings and what goes on around him.”

Meeting the right doctor

Initially, I did not incur any costs for treatment since Dr Justus Byarugaba, a neuro paediatrician at Children’s Centre in Bugolobi, was doing research on autism and would only charge me for consultation.

Dr Byarugaba referred us to Mulago National Referral Hospital for further tests. He made appointments and although the queue of children waiting was long and only one consultant carrying out that particular test, I was patient.

A series of tests were carried out which were both emotionally and financially draining. “It has been a long time, I cannot remember the figures but my family members and well-wishers supported towards this. Fortunately, Komo was not taking any medication until he developed seizures at 14,” she says.

“He is now taking medication which costs Shs4,000 every day. In the beginning he had to be guided on how to take the medicine but now he knows he has to take it twice a day, after breakfast and dinner. The drugs are available and the cost is met by his family and well-wishers,” Kaleeba adds.

Education

Kaleeba says when Komo turned four, a friend recommended that she enrols him at Kissyfur Daycare School in Entebbe because the head teacher was knowledgeable about autism and how to handle children who had it.

“He was there for two years but they could nolonger manage him because he would become aggressive and sometimes wander off. Many times teachers would call while I was at work that they could not find him,” Kaleeba says.

“The parents started fearing for their children and since the school did not have a fence, it was hard for the teachers to keep watching over him. They advised me to look for another place for him,” she adds.

Kaleeba says she had to quit her job at The AIDS Support Organisation (TASO) to look after her child because she had reported to police several times that he had wandered off and would find him at the lakeshore staring at the water. The mother says her boy needed to interact with other children but she had nowhere to place him. This was the time she thought of starting a place that would not only help him and other children with autism but also normal children.

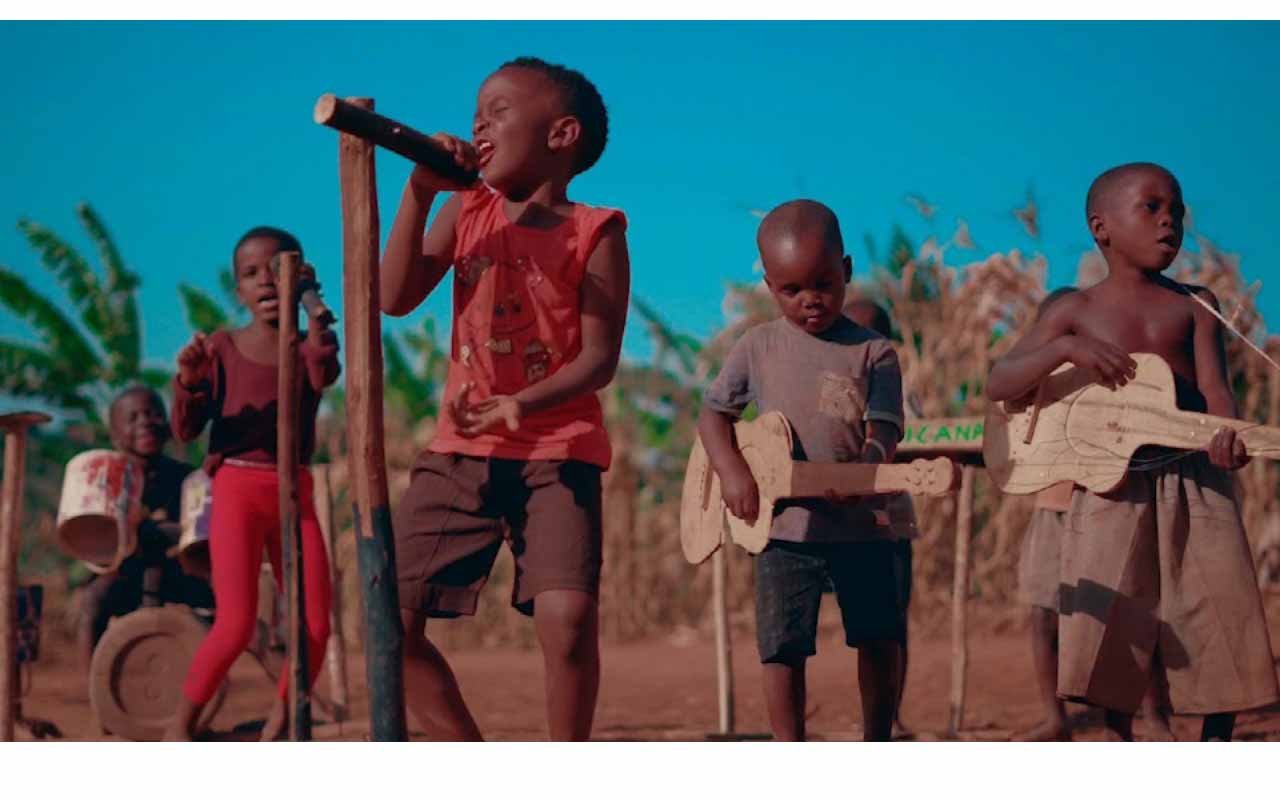

Some of the autistic children at the Komo Centre. They are given life skills and helped to get employment. Photo by Godfrey Lugaaju

Family support

“I got all the support I needed from my family. He knows he is loved, wanted and appreciated just like his siblings. Komo has matured and rarely seeks attention which has made it easy because there are no more sibling fights,” she says.

Kaleeba adds that as a family, they create time to make him feel special. We set days to take him out and engage him in activities which expose him to live outside home and school environment through outings, travel and the like.

“He turned 20 on April 18, so I took him away on a work trip, he sat patiently while I worked, we went out for walks and dinner in the evenings and I mostly explained to him mostly about what it means to turn 20. Although I got no response, I always got a smile at the mention of the word birthday,” she says.

Helping other children

Kaleeba started the Komo Centre for Understanding Autism (Entebbe) in 2007 because she wanted to start a facility where her child would be provided with a secure, accepting environment. Initially it was a day care centre which gave him an opportunity to leave home and go to play and have someone watch over him. With time it progressed to use of Individual Education plans which ensure that he is actively engaged while at the centre from class work to social and life skills. “The centre is mainly for children with Autism as we do not have the capacity to take on children with other disabilities. We also focus on teaching skills for older children with autism so they can be gainfully employed,” Kaleeba says.

What the centre does

Kaleeba says it is a special needs school with a section for normal children up to six years only and currently there are 13 children enrolled. However, she adds that over the years, they have supported more than 100 families directly or indirectly. “Since autism affects the children differently, we are able to engage each child in activities that they can achieve,” she adds.

She adds that the centre follows the normal school calendar days although home interventions such as home visits, outings during the holidays to give the parents some kind of respite are carried out. The curriculum is self-developed and mainly focuses on attaining life skills and social skills and a bit of writing, reading depending on the ability of the child established through an initial observation period after which an IEP is developed.

“We have also partnered with interested organisations that offer our older children a chance to work for example in farms and recreation areas and are working towards them being remunerated for the work that they do. The challenges come with getting them to these establishments and availability of work buddies as most of them cannot perform tasks independently,” she says.

How autism affected him

Christine Kaleeba says her son has to be guided most of the times especially for activities out of his routine. Outings such as shopping, travelling are guided. “He, however, learns a lot from observation. He for example taught himself to swim at four years and is now a very good swimmer who likes to race with random people he meets in the pool,” she says adding: “He is fairly independent in regards to taking his medication, which he religiously takes every morning and evening but if it is not in the usual place or is finished, he cannot communicate that information so that has to be monitored to ensure his supplies are available and in the usual place.”

Kaleeba adds that Komo does certain things out of routine and the need to have a clean environment. For example, he always makes sure the sink is clear of dirty dishes, which he washes and later cleans and puts away. He does not like disorder or untidy environments, does not understand that his sisters need to play with their toys therefore is forever putting away their toys.

He can get violent especially if his space is intruded upon like if someone sits in the one chair that he uses in the living room. He is, however, becoming more tolerant but might remain standing for example until the person vacates his seat.