Prime

The burden of proving a false HIV diagnosis

What you need to know:

- When a complainant has led evidence establishing his or her claim, the complainant has executed his or her the legal burden. The evidential burden then shifts to the defendant to rebut the complainant’s claims.

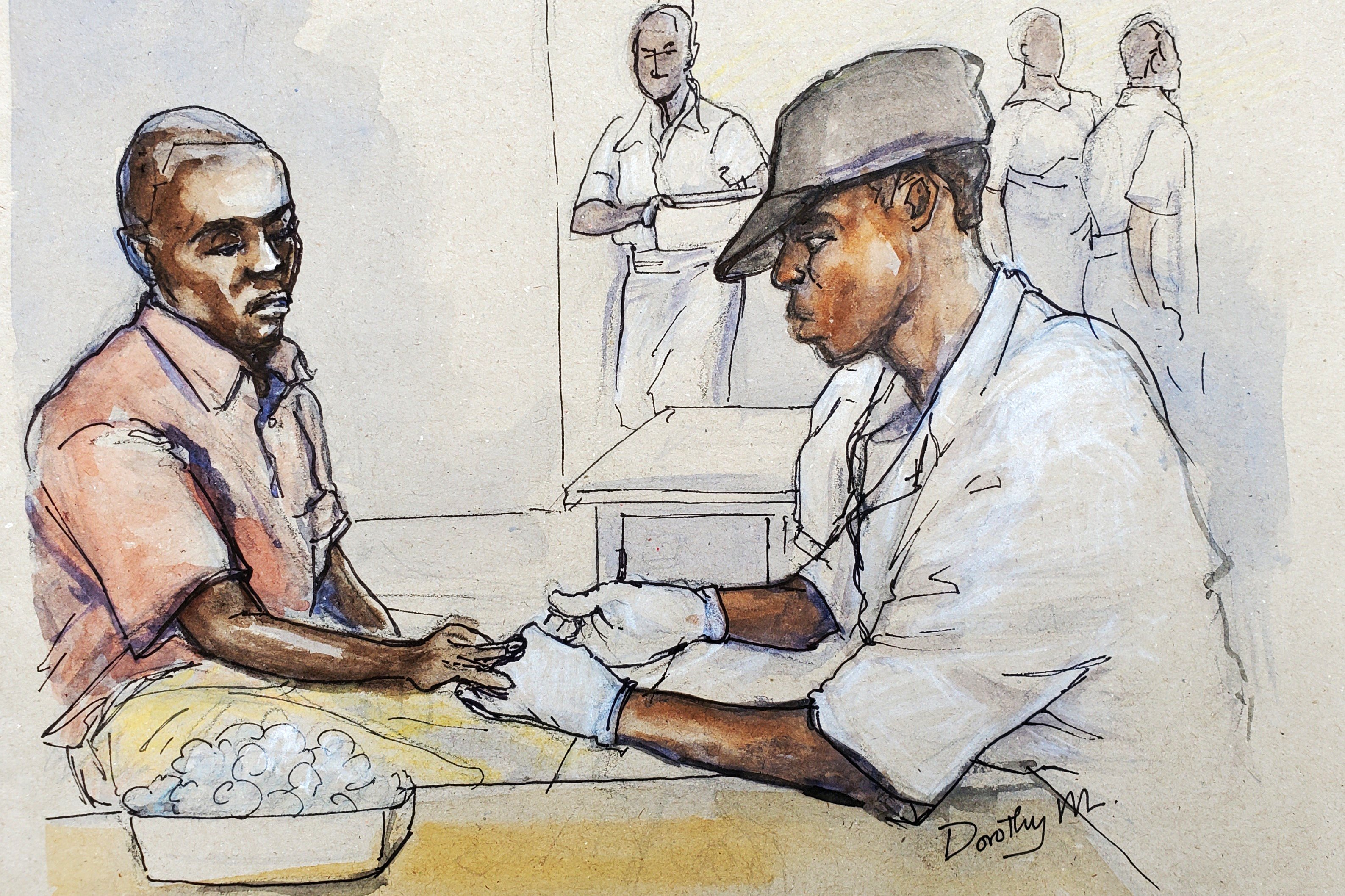

For more than one year Mr Okaka Denis bore the agony of a false HIV diagnosis. He was diagnosed as HIV positive when he went for an HIV test in a laboratory belonging to AAR Health Services (Uganda) Limited on March 29, 2007.

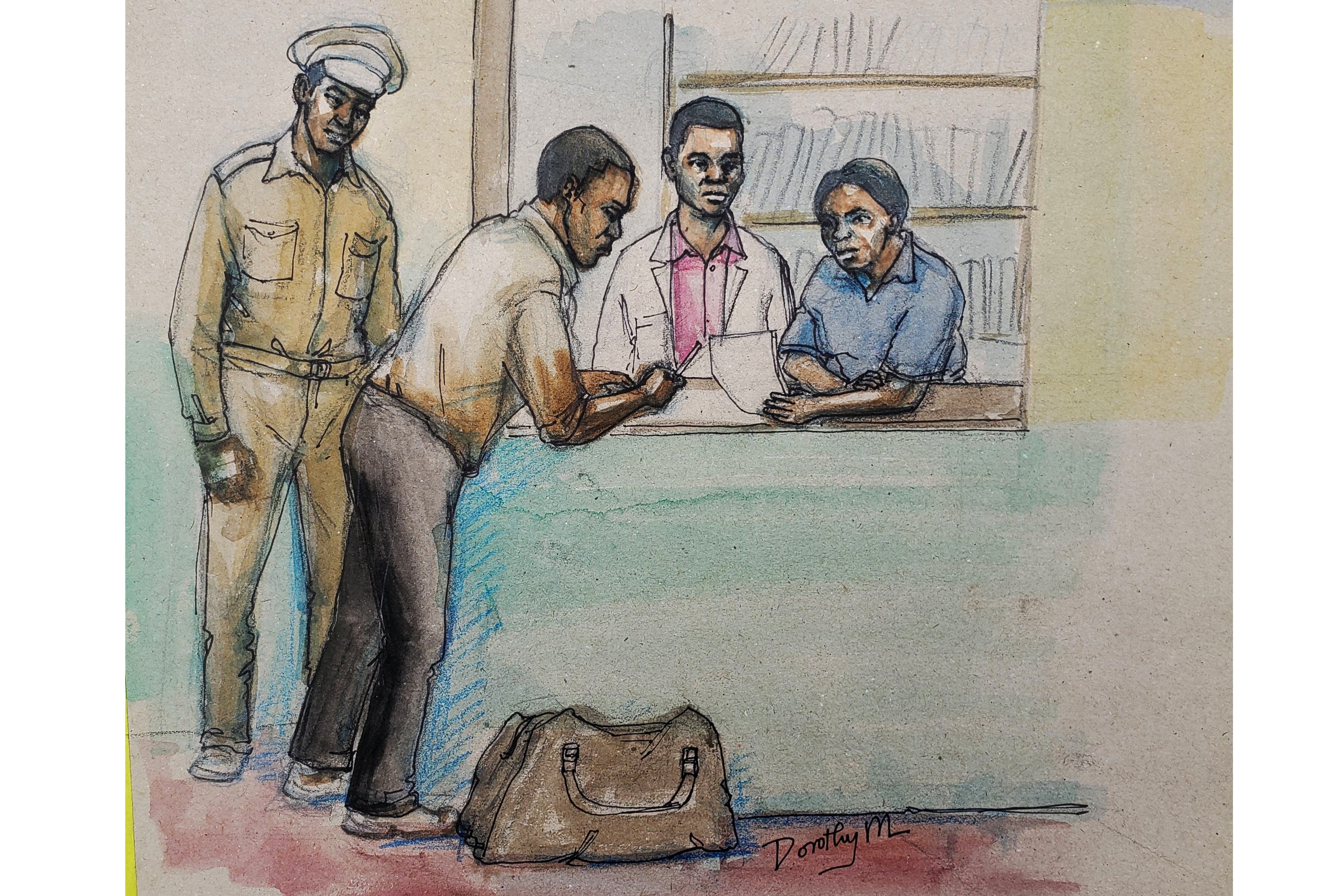

However, in May, 2008 he was found to be HIV negative after three tests were carried out in a different health facility. Mr Okaka did not take his agony lying down; he instituted legal proceedings against AAR Health services.

Legal proceedings

The main issues before court were whether AAR’s laboratory staff were negligent in carrying out the HIV test and whether the patient contributed to his agony (contributory negligence) when he failed to heed advice from

AAR to undertake routine short spell HIV tests to establish or confirm his HIV status. In civil cases the burden of proof lies upon the person who alleges an issue. In this particular case the burden was on Mr Okaka to prove to court that AAR’s laboratory wrongly carried out the HIV test and gave him a false result.

And the law is that the person who desires any court to give judgment in his or her favour is duty bound to prove his or her facts.

Burden of proof

The burden of proof as to any particular fact lies on that person who wishes court to believe in its existence. The law, however, goes further to clarify between a legal burden and an evidential burden.

When a complainant has led evidence establishing his or her claim, the complainant has executed his or her the legal burden. The evidential burden then shifts to the defendant to rebut the complainant’s claims.

The standard of proof in civil proceedings is on a balance of probabilities. Putting this simplistically court will decide the case on who presents a more persuasive case or evidence.

The burden rested on Mr Okaka to prove to court that he was not only given a false HIV result but that the procedure to carry out the test did not conform to known medical guidelines.

The patient’s lawyer submitted to court that the laboratory technicians employed by AAR failed to adhere to the medically stipulated procedures when carrying out the said HIV test on his client.

Misdiagnosis of HIV

Failure to adhere to the guidelines was what led to the misdiagnosis of HIV infection in his client, the lawyer emphasised. However, the lawyer acting for AAR told the court that whatever was done by the laboratory to Mr OkakaDenis in this case was clearly what any reasonable medical establishment would and should have done in similar circumstances.

Court defined negligence as failure to do something which a reasonable man would do or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. Court further defined medical negligence as an act or omission by a medical profession that deviates from the accepted and orthodox standard of care.

The legal standard of care expected of medical professionals is what is expected of their professional peers or someone with a similar training and experience.

Where some special skill is required, the test for negligence is not the test of the ordinary man on the street as the ordinary man has not this skill; the test is the standard of the ordinary skilled person exercising or professing to have that special skill.

It is the duty of a professional to exercise such skill and care in the light of his or her actual knowledge. A skilled person cannot be judged by reference to a lesser degree of knowledge than that of the ordinarily skilled practitioner.

To court this standard of care is especially applicable where the skilled people such as medical professionals cause harm to patients as a result of lack of knowledge or awareness.

Courts will want to establish the degree of knowledge or awareness which the professional ought to have in that context. A skilled person would be found liable for a wrong if, in spite of the special knowledge, that the danger or harm caused was not reasonably foreseen.

The issue in such a case is whether the skilled person acted in accordance with practices which are regarded as acceptable by a respectable body of opinion in his profession.

It is now a widely accepted legal opinion that a medical professional can be held guilty of medical negligence only when that person falls short of the standard of reasonable medical care.

Negligence

A doctor, for instance, cannot be found negligent merely because in a matter of opinion he made an error of judgment. When there are genuinely two responsible schools of thought about management of a clinical situation, the court would do no greater disservice to the community or the advancement of medical science than to place the hallmark of legality upon one form of treatment.

To establish a claim of negligence Okaka had to establish to court that AAR owed him a legal duty of care, which duty was breached and as a result of that breach he suffered injury or harm or some form of damage.

The onus was also on him to prove that the breach of duty was the direct or proximate cause of his injury. A proximate cause of injury is that which would automatically or naturally arise from such a breach, unbroken by any intervening event and without which such an injury would not have occurred.

Okaka had to prove to court that there was an approved and standard way of carrying out an HIV test.

He had, further, to prove that the laboratory staff working in AAR’s lab did not follow the usual procedure but that the laboratory staff instead adopted a practice that no professional or ordinary skilled person would have taken.

To be continued

Courts will want to establish the degree of knowledge

Dr Sylvester Onzivua

Medicine, Law & You