Prime

Challenges encountered in post-mortem examinations

What you need to know:

- One of the elementary challenges with a forensic post-mortem examination is the correct interpretation of observations made on external and internal examination of the body organs, and more so the neck in suspected cases of strangulation or death as a result of injury to the neck.

The post-mortem examination, and especially the forensic post-mortem examination, is often not without challenges.

A forensic post-mortem examination involves obtaining information about the death and circumstances thereof, external observation of the body, examination of the internal organs and other auxiliary examinations.

One of the elementary challenges with a forensic post-mortem examination is the correct interpretation of observations made on external and internal examination of the body organs, and more so the neck in suspected cases of strangulation or death as a result of injury to the neck.

On the morning of September 10, 2017, a 37-year-old housewife was found unresponsive on her matrimonial bed and was taken to hospital but confirmed dead 30 minutes later after a rigorous effort to resuscitate her failed.

Dr Sylvester Onzivua. Forensic pathologist. Photo/Courtesy

Post-mortem examination

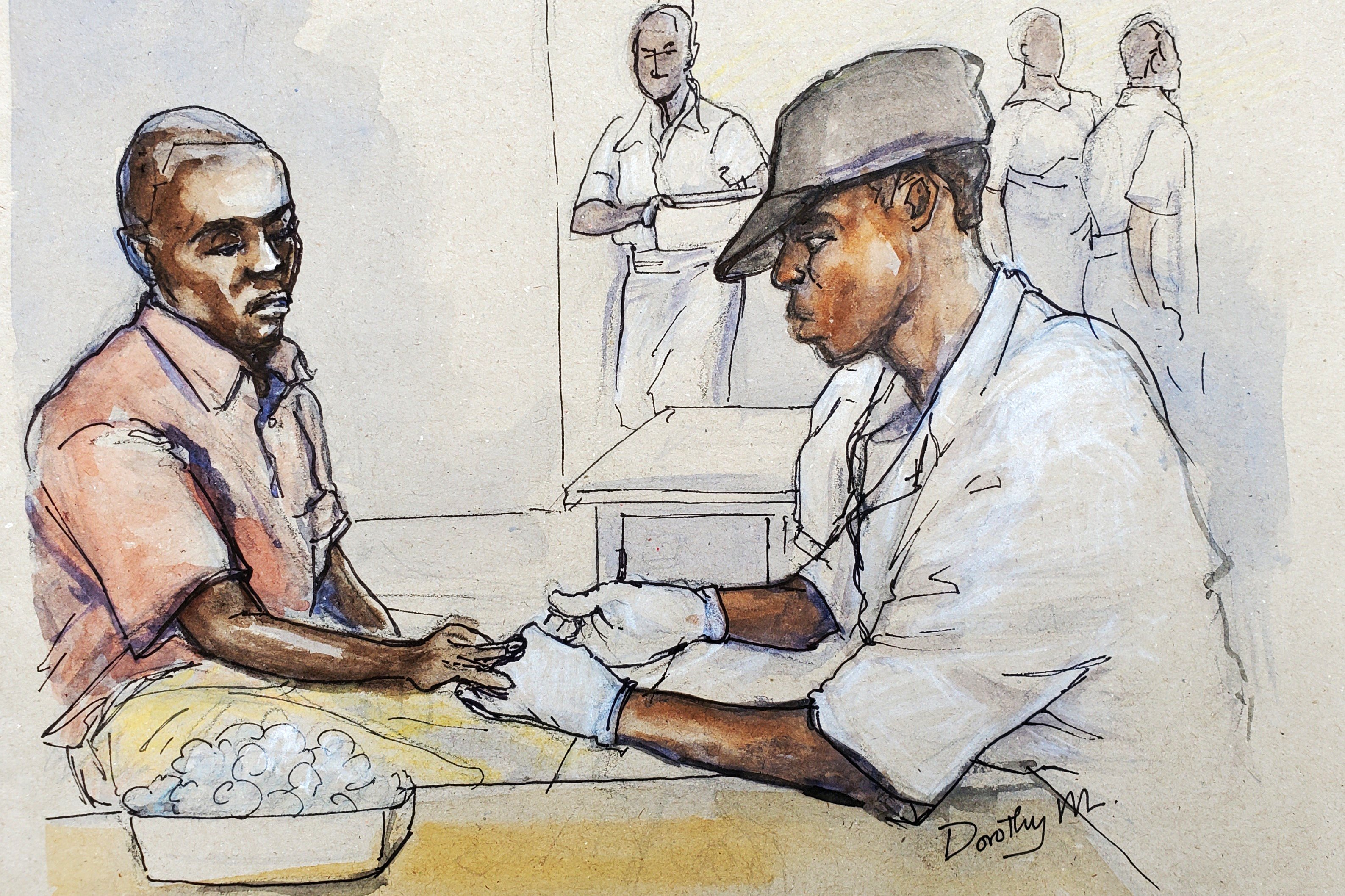

A post-mortem examination was carried out on the body by a pathologist, who concluded that the injuries found on the neck of the deceased were indicative of manual strangulation.

The husband of the woman, a retired military officer, was convicted of murder of his wife and handed a life sentence. The husband of the deceased, however, contested the post-mortem report and appealed against the conviction and the sentence.

The neck poses considerable difficulties to the doctor during a post-mortem examination as there are a number of important structures in the neck that have anatomical variations and characteristics that make differentiating artefacts from real pathologic findings challenging. Abnormal bleeding may also be encountered in the neck and this may not be related to trauma at all but has sometimes been misinterpreted as traumatic.

Bloodless neck dissection

Over the years, forensic pathologists have developed a technique known as the bloodless neck dissection to mitigate the pitfalls associated with interpretation of post-mortem findings in the neck. This involves removal of the brain and organs in the chest before dissecting the muscle layers of the neck.

The removal of the brain and other organs drains blood away from the neck and minimises the chances of artefacts of blood in the neck. The neck muscles are then carefully dissected layer by layer to achieve maximum exposure of the neck.

There is a U-shaped bone in the neck called the hyoid bone, and the fracture of this bone is an indication of strangulation. Fractures are diagnosed when a bone is found to be discontinuous.

However, this bone develops and matures in a segmented fashion and may appear to be fractured while in truth this is a developmental anomaly.

An important feature of a true fracture of this bone is bleeding and this must be documented. X-ray examination of the bone, as well as histology, are important adjuvant investigations in challenging cases. There are also some cartilages near this bone that may be mistaken for fractures.

Haemorrhagic artefacts

Haemorrhagic artefacts are common in the neck and have been the subject of many studies by forensic pathologists. Blood can seep from the blood vessels into the muscles of the neck as a result of dissection and this may mimic bruising related to trauma. This is particularly so when there is congestion of the neck vessels and when the blood vessels themselves decompose after death.

The cardinal function of the heart is to pump blood in the body and when death has occurred, blood remains stagnant in the blood vessels. This blood is pulled by gravitational force to the most dependent parts of the body and this is influenced by the position of the body after death, especially if the body is in a prone position.

When the blood vessels start to decompose, this blood again seeps out of the vessels and may be misinterpreted as bruising. It can be difficult to differentiate the haemorrhages associated with pooling of blood due to gravity and that caused by strangulation. However, the diagnosis of strangulation can usually be correctly ascertained by careful examination of other structures of the neck, as well as the presence of external injuries on the neck.

There may also be injuries that occur in the neck due to resuscitation efforts. The common injury occurs when there is an attempt to insert an intravenous central line in the neck. The muscles in the neck may get injured in the process and these results in some bleeding which may be misinterpreted.

Inserting a tube in the trachea of a patient may also cause injury to the structures of the neck. There may also be fracture of the larynx due to pressure applied during resuscitation. The housewife in question was resuscitated for 30 minutes after she arrived in hospital.

Cause of death

Strangulation will usually result in compression of the blood vessels in the neck and subsequently congestion of blood vessels in the face and eyes. This will ultimately lead to rapture of some blood vessels, seen as haemorrhage in the face and eyes. These shortcomings were pointed out by a forensic pathologist who was asked to review the post-mortem report of the housewife.

The initial post-mortem report indicated that there was accumulation of blood in the abdomen, chest cavity and in the sac containing the heart. This, to the forensic pathologist, led to a question of whether the deceased had a pre-existing disease that led to bleeding in these body cavities.

The pathologist also attributed the death of the housewife to airway obstruction. This would have led to poor entry of oxygen into the body, making the blood take on a bluish colour also known as cyanosis.

The doctor stated in no uncertain terms that the trachea was intact with no injuries. In cases of strangulation leading to airway obstruction, there are usually injuries to the trachea.

It was documented in the report that the blood vessels of the deceased must have been obstructed due to the manual strangulation. The doctor did not, however, indicate or note any injuries that might have occurred to the blood vessels. Again, the force that is required to obstruct the blood vessels in the neck would have been severe enough to cause injuries to other tissues in the neck.

It was also unfortunate that the pathologist who carried out the initial post-mortem did not aggressively look for and document defence injuries in the deceased. These injuries are a reflex attempt of an assault victim trying to put up a defence. Could this, therefore, be a case of a miscarriage of justice?

To be continued

Dr Sylvester Onzivua

Forensic pathologist