Prime

Here’s the space Mayanja saw Parliament occupying

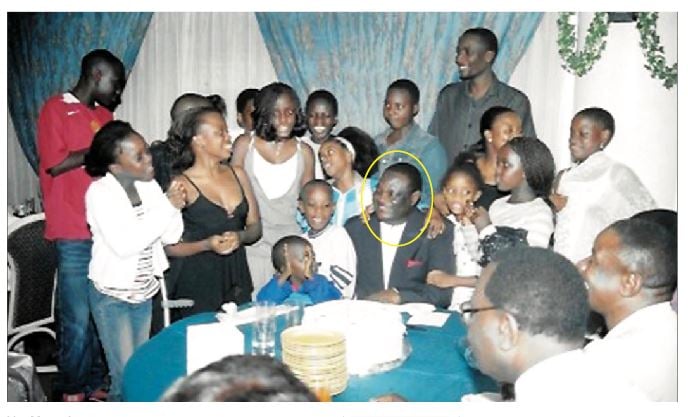

Abu Mayanja (centre) at a Muslim religious gathering with Prince Nakibinge (left), and other leaders. PHOTO/COURTESY

What you need to know:

- Abu Mayanja thought that prolonging Parliament for five years without going back to the electorate was not good.

- He thought Members of Parliament represent the wishes and interests of the voters, and prolonging Parliament for five years meant that members were more interested in staying in power than serving the electorate. In the eighth instalment of the serialisation of Prof ABK Kasozi’s book, the historian outlines the role Mayanja envisaged the House playing.

Abu Mayanja thought Parliament symbolises the highest concept of representative government and institutions. As such, only elected people should be Members of Parliament (MPs). He thought the proposals which gave the President power to nominate a third of MP would kill the concept of representative government.

He advised Parliament to set the number of MPs a person must get to be President if Parliament was to be the electoral college for choosing a President.

Mayanja felt Parliament, as a watchdog of the people and their liberties, should be informed every month of the people detained by the minister responsible.

“Mr Speaker, before I leave this chapter, there has been a provision which has not been followed in the past. That is the provision whereby a minister is required to make a report to Parliament every month if Parliament is in session, concerning the people who have been detained under a State of public emergency,” he said on the floor of the House during the enactment of a new Constitution on July 6, 1967.

“Now if my recollection is correct, under the existing Constitution, the minister must inform us how many people are actually detained, and how many are being detained contrary to the recommendations of the tribunal so that we can know the number of people who are being detained on the fiat of the minister alone after the advisory tribunal has recommended that they should be released.”

He further offered thus: “But I think it is of the utmost importance that this House should be aware as a watchdog over the liberties of the people, or such liberties as they may possess during the state of emergency. It is this House which authorises that the emergency should continue in force. It is this House which can revoke a state of emergency, although the President can also revoke it. It is this House which approves such regulations, or such extraordinary measures as may be taken during a period when a public emergency is in force.”

Mayanja considered protecting taxpayer’s money and other national resources as one of the most important functions of Parliament. He emphasised that Parliament authorises the use of public funds when it resolves itself in a Committee of Supply, considers government proposals (often contained in a budget or supplementary requests) and approves or rejects them.

Role of the House

While discussing the report of the Uganda Electricity Board (UEB), Mayanja urged those responsible for Government Business to table reports as soon as possible so that members do not discuss issues that were no longer relevant. For example, the UEB report, which was tabled for discussion, was old.

While discussing the marketing of minor crops, Mayanja pointed out that it was the role of Parliament to pass just and fair laws and members of the Opposition were expected to check [the] government whenever unfair or discriminatory Bills were tabled for debate. In this case, the government wished to make a law where the minister of Agriculture would apply a marketing law differently in each part of Uganda. This Mayanja opposed. He emphasised that the role of Parliament was not only to make laws but to make good laws.

“Mr Speaker, if I am mistaken, the purpose why I am here and the reason why I am paid to be here is to voice such views so that we can have a correction. This is not the first time that a piece of legislation has been passed with empulunguse—with certain things which were not meant to go into it,” he opined.

Dos, don’ts

In later years, Mayanja criticised both the Speaker and the Executive arm of government for involving Parliament in the arrest of two Acholi MPs, Reagan Okumu (Aswa County) and Michael Nyeko Ocula (Kilak County).

Mayanja complained about MPs who did not fulfil their duties as speakers, scrutinisers of reports or ideas in Parliament. He thought the role of an MP is not only to vote, to pick allowances and go home. According to him, an MP must fully participate in the proceedings of the House and should not expect a pension or gratuity because being an MP is a political job and ends when one ceases to be an MP.

Book cover.

Mayanja insisted that the people were supreme over Parliament and the Executive arm of government. They alone had the power to constitute Parliament by electing or rejecting a person aspiring to be an MP. MPs had no power to expel from Parliament a person elected by the people (see Chapter 11, item 6 for Mayanja’s words).

Mayanja also felt Parliament should not have a right to elect members to the House. He insisted that allowing nominated and, especially elected people to sit in Parliament contradicts and makes a mockery of the concept of representative institutions. He thought that only members elected by the people should sit in Parliament because that organ of government must be made up of representatives of the people.

For the people

Mayanja noted that Parliament is a civilian institution where people’s representatives meet to discuss state affairs. He insisted that it represents people as individuals, not as corporate bodies. He felt that keeping the UPD’s representation in Parliament was “unsound and unfortunate as the decision itself.” He thought that by making soldiers sit in Parliament as representatives of a government institution, the state was giving a legal window for involving soldiers and, therefore, the army in politics. However, soldiers who opt for civilian life should be allowed to run for and sit in Parliament.

Mayanja insisted that Parliament had no moral basis for prolonging its life. He felt that since the people were the only constituency that had the power to constitute Parliament, members of the House had no legal basis to prolong their terms of office.

On the Westminster model

In the first eight years of the Uganda postcolonial state, Parliament tried to imitate the Westminster model. However, it increasingly became a rubber stamp institution as the Executive branch grabbed Parliament’s powers through force, patronage, or corruption.

Despite that, efforts were made by some individuals to make Parliament work as a legislature modelled on Westminster. Mayanja, possibly more than any other MP, knew how the British Parliament worked. His six years at Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn helped him understand how the Westminster model operated. He kept the British Parliamentary traditions in Uganda’s legislative body alive, although he struggled to put an African touch on Parliament’s behaviour without success.

The colonial officers who insisted that he go to the UK instead of the USA or India for his degree studies must have been pleased with his performance in Parliament. He spoke his mind eloquently without fear of likely ugly consequences, as the reader will find out as this book proceeds. When he was arrested in 1968, the British High Commission was concerned, and in the many communications sent home, Mayanja was regarded as a foremost intellectual and an outstanding parliamentarian.

During debates on the 1967 draft Constitution, he spoke for eight hours each day for three days. A writer in the New Vision referred to Mayanja as the jewel in his contributions to Uganda’s Parliament from 1964 to 1968.

Parliamentary traditions of the UK House of Commons were thought by Mayanja and other Members of the Ugandan Parliament to apply to their own. When Mayanja addressed Ms Lubega, MP as Hon Friend and some members were intrigued over the address, he was forced to explain to them that it is parliamentary courtesy to address a member sitting on the same side as “Hon Friend.”

Mayanja thought MPs should be decently dressed but did not say who sets the decent standards, probably implying that everyone knows that it was a Westminster model requirement to dress well.

Thought

Mayanja felt Parliament, as a watchdog of the people and their liberties, should be informed every month of the people detained by the minister responsible.

“Mr Speaker, before I leave this chapter, there has been a provision which has not been followed in the past. That is the provision whereby a minister is required to make a report to Parliament every month if Parliament is in session, concerning the people who have been detained under a State of public emergency,” he said on the floor of the House during the enactment of a new Constitution on July 6, 1967.