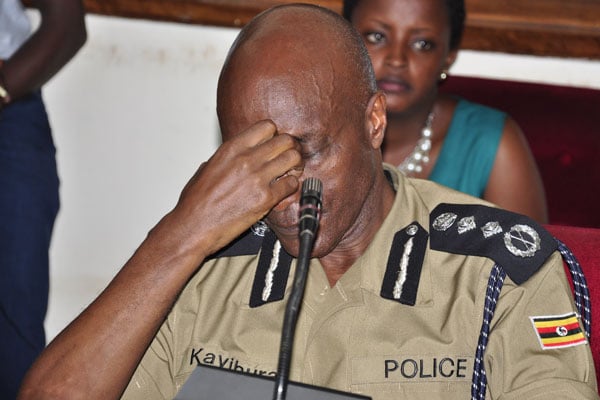

Former police boss Kale Kayihura. PHOTO/FILE

|National

Prime

How Gen Kale Kayihura became so powerful

What you need to know:

- Rise and fall: Former Inspector General of Police retires from the army this month, bringing an end to a career which saw him emerge from the bushes of Luweero to become a powerbroker at the highest echelons of government before he fell so dramatically.

Many illustrious names figure on the list of the most daring National Resistance Army (NRA) fighters. The fighters were nicknamed ‘Kalampenge’ because of the unexpected valour with which they challenged Apollo Milton Obote’s Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA).

Top on that list is Gen Salim Saleh. President Museveni’s brother nearly lost his life at the famous battle of Bakalabi, where he met a well-prepared UNLA unit that had assumed good positions. The Kalampenge in Gen Saleh did not allow him to retreat in silent resignation. He took a bullet for his troubles. Many think it could have been worse.

Maj Gen Matayo Kyalingonza was also the very embodiment of a Kalampenge. After the February 6, 1981 attack on Kabamba Barracks ended in fiasco, with most of the guerrillas heading to Kiboga District to hide, Kyaligonza went to Mukono. His mission was to stage ambushes immediately as a deflecting ploy. Kyaligonza, who carried out urban guerrilla warfare by attacking police stations and trying to light gas stations, had the role of diverting attention from Museveni’s rebels.

Kyaligonza’s battalion, named Black Bomber, fought in the areas of Mpigi and Kibibi before it eventually advanced to Kampala from Hoima Road. His force attacked and captured, among others, Makindye Barracks.

Defendant. Maj Gen Matayo Kyaligonza. PHOTO/FILE/ALEX ESAGALA

There was also Gen David Sejusa (Tinyefuza), who was incarcerated during the Bush War until March 1985. This was after he was charged with insubordination, having openly criticised guerrilla leader Museveni. Sejusa was ultimately released and, when the war intensified in the west and central regions, was selected as the general commander of the units that captured Hoima, Masindi, and Karuma Falls before moving up to northern Uganda.

Although he came to typify what National Resistance Movement (NRM) stood for, Gen Edward Kalekezi (Kale) Kayihura was neither among the elite commanders nor fighters during the Bush War that lasted five years. Born in the southwestern district of Kisoro in 1955, Gen Kayihura joined the NRA guerrillas in the Luweero jungles in 1983. This was three years after Mr Museveni and his ragtag rebels had declared war against Obote, who they accused of stealing the 1980 General Election.

From London to Luweero

Gen Kayihura swapped the neon lights of London, UK, where he had obtained a master’s degree in law at the elite University of London, for the lanterns in Luweero’s jungles. Those who know him say he had planned to do doctoral studies in law, but remarkably found himself in the bush. He first worked as an aide of Gen Saleh and would later take on the commandership of the mobile brigade from 1982 to 1986.

Aged just five, Gen Kayihura lost his father—John Kalekezi—to a plane crash in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. Kalekezi was one of Uganda’s nationalists who fought for independence. Much like his son would look in adulthood, Kalekezi was slender and tall. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in veterinary medicine from Makerere University.

Kalekezi and his assemblage first announced their opposition to colonial rule when they protested Queen Elizabeth II’s visit in 1954.

Kalekezi’s gang went as far as stealing 30 rifles and several bullets from the Kisubi armoury in an effort to face off with the colonialists.

The guns were, however, recovered by the colonial government before the Queen set foot in Uganda.

Born in Kisoro in 1932, Kalekezi traversed the continent spreading the gospel of Pan-Africanism. In doing so, he rubbed shoulders with Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s former president.

If Kalekezi’s military endeavours suffered a stillbirth, Gen Kayihura’s were successful. After emerging victorious from the Luweero jungles, Kalekezi Jr—who would soon go by a shortened variant of his father’s name—served as staff officer in the Office of the Assistant Minister of Defence from 1986 to 1988.

Kale the NRM cadre

Earlier, he had served on the Constitutional Commission following an appointment by Mr Museveni in the capacities of chief political commissar, and director of political education in the NRA (later to be known as Uganda People’s Defence Forces or UPDF).

Recognition. President Museveni decorates Gen Kayihura during Independence Day celebrations in 2016. FILE PHOTO

It was during his tenure as a member of the Constitutional Commission—charged with soliciting views that would be incorporated in the draft of the current Constitution—that Gen Kayihura’s very strong NRM views surged to the fore.

In his 2005 book titled The Search for a National Consensus: The Making of the 1995 Uganda Constitution, retired Chief Justice (CJ) Benjamin Odoki, who led the commission, tried to contrast Kayihura and Lt Col Sserwanga Lwanga—another soldier who Mr Museveni dispatched to be part of the commission.

ALSO READ: The fall, rise of Gen Kayihura

Although he was a confidant of Mr Museveni, having served as his earliest principal private secretary, Mr Odoki describes Lwanga, who died in 1995, as a person with “balanced views and did not have to support the NRM blindly.”

It was not lost on the CJ emeritus that Lwanga “always explored alternatives” and generally came off as “an extremely respectful soldier who, during this dreary process, exhibited principled compromise and patriotism.”

This was in stark contrast, Mr Odoki noted, with Gen Kayihura who, despite being “sober and soft-spoken … presented very pointed and thoughtful arguments.” Kalekezi Jr also made it abundantly clear that he was “a freedom fighter and a believer in the objectives of the Movement struggle and politics.”

According to Justice Odoki, whilst Gen Kayihura did not impose his partisan views on any member of the team, since the working rule was that they were not on the team to promote the views and interests of those they represented, it’s apparent that the future Inspector General of Police (IGP)—unlike Lwanga—was on this commission to do classic intelligence work for Mr Museveni.

Congo war

By 2002, Kayihura had risen to the rank of Brigadier. When the Second Congo War took centre-stage, he found himself sucked into it. In 1997, Uganda joined forces with a number of African countries, including its tiny neighbour Rwanda, to end Mobutu Sese Seko’s 32 years of control over the mineral-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The victorious parties wasted no time in installing Laurent-Désiré Kabila to run the rule over the DRC.

A file photo taken on December 01, 1973 in London shows former Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko with Britain's Queen Elizabeth II.PHOTO/ AFP

After a short honeymoon, Kabila made a U-turn in 1998. He consequently ordered Rwandan and Ugandan forces to leave the eastern DRC, fearing annexation of the mineral-rich territory by the two regional powers. Kabila, who had received military support from Angola and Zimbabwe and other regional powers, was assassinated by his bodyguard in 2001. He was subsequently succeeded by his son, Joseph Kabila.

Although Kabila Sr had ordered UPDF out of the eastern DRC, Ugandan authorities were quick to turn a deaf ear. They held that their presence was merited by the continued presence of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) in the tinderbox that was the eastern DRC.

It was under that context that Kayihura was dispatched as an operational commander of the UPDF forces in Ituri Province in the DRC. The UPDF, however, ended up fighting with Rwandan forces, which had also camped there furthering their narrow-minded interests and other Congolese militia groups.

In Ituri Province’s capital Bunia, Gen Kayihura would soon run into Thomas Lubanga, the warlord who commanded the Patriotic Force for the Liberation of the Congo (FPLC). This was by all measures an anti-Kabila outfit. Lubanga had been pro-UPDF when he was still under the Congolese Rally for Democracy-Liberation Movement (RCD-ML) led by one Mbusa Nyamwasa.

Lubanga, however, broke ranks after he was sidelined. He quickly put together the FPLC, which had a sizeable fighting force.

It didn’t take long for Lubanga to become weary of the UPDF. In fact, he soon ordered Kayihura’s troops out of the entire Ituri region, to which Kayihura obliged. Yet it would soon come to light that Lubanga’s men had taken Kayihura capitive. It reportedly took the efforts of Gen James Kazini (RIP), then the army commander, to pull Kayihura from the crosshairs. The reinforcements Kazini is reported to have sent in came in handy.

READ HERE:Friends abandoned me - Kayihura

Kayihura later denied troop reinforcements sent to him while overseeing UPDF operations were meant to rescue him from Congolese rebel captivity. He instead claimed that the UPDF reinforcements were meant to foil an anticipated counter-attack from Lubanga and his allies, who had been driven out of Bunia in March 2003.

Upward trajectory

With its tail firmly stuck between the legs, the UPDF left the mineral-rich eastern DRC amidst looting claims. Kayihura’s career would take an upward trajectory. For starters, he was assigned by Mr Museveni to be his military assistant. He would also head the anti-smuggling unit called the Special Revenue Protection Services (SRPS) charged with curbing smuggling.

Then Inspector General of Police Gen. Kale Kayihura appearing before Parliamentary Committee on defence on February 4, 2014 to answer queries about the conduct of Uganda police force. FILE PHOTO

There were legal queries about how Mr Museveni formed the SRSP, with the 2001/2002 Auditor General’s report poking holes into the eligibility of the unit, its legal framework, budget authorisation, and the accountability of funds allocated to it.

From July 2001 to February 2002, the Auditor General said Kayihura had spent Shs1.9 billion on SRPS to facilitate its operation. These funds, the Auditor General’s report added, were not budgeted for and were reportedly paid on verbal instructions from the Finance minister.

Another charge brought against the SRPS was that it couldn’t give a proper account of the goods it would impound. It wasn’t clear where the goods would be taken or where the proceeds from their auction were kept. During the six years of its operation, SRPS confiscated billions of shillings worth of goods from suspected smugglers and other wrongdoers, but many of the goods were reportedly not turned over to the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA). This was partly because Kayihura’s men operated as a separate entity, only complementing the tax man’s role in tax collection and administration.

SRPS stain

Furthermore, the SRPS, which was a combination of UPDF personnel and detectives from the police, was accused of gross violation of human rights, with the residents of eastern Uganda, especially Busia, Tororo, Bugiri, and Iganga districts bearing the brunt of Kayihura’s men.

Kayihura had a different perspective. He bragged before Parliament about how this unit had enabled URA to recover Shs34.7b in revenue from the start of the millennium onwards. It took the 2006 General Election for Mr Museveni to disband the SRPS as the public laid out the human rights violations to the President, who was on the campaign trail.

When Kayihura was performing his various roles, as Mr Museveni deemed fit, the 2001 General Election happened. The autopsy of the violence-riddled elections that pitted President Museveni against his former physician, Dr Kizza Besigye, showed something that Mr Museveni found unpalatable. It emerged that Dr Besigye had outclassed Mr Museveni at many polling stations in the country from where police personnel voted, Mr Museveni went into a rage and vowed to clean up the Force.

“Many policemen would rather vote for a jerry can than for me,” Museveni said back then before instituting a commission of inquiry into the Force.

The Justice Julia Sebutinde-led probe excavated dirt, sly dealings, incompetence, and corruption within the Force. It recommended radical measures, including sacking some of the senior officers.

Mr Museveni then swiftly appointed Gen Katumba Wamala, an illustrious UPDF officer, to lead the clean-up. The appointment of Gen Wamala, who had fought Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels in the north, to superintend police—which in theory is supposed to be “a civilian force”—led to all sorts of speculation. Although popular belief was that he had been appointed to “NRM-ise” and militarise the Force, Gen Katumba wisely steered away from politics and tried to act professionally.

One of the most enduring memories of Gen Wamala’s short-lived reign was a fundraising campaign he undertook to purchase police patrol pick-up trucks. This made him popular among the public, who contributed generously to the cause. Yet, at best, the campaign brought to the fore Gen Wamala’s struggles on the job—the fact that he did not have adequate resources to run the Force efficiently. His replacement—who came in late 2005—would not face such travails. Kayihura, whose appointment as IGP came with the new rank of Major General, would waste no time in throwing his weight around.

Former IGP Kale Kayihura and the wife Ms Angella Kayihura at a function in 2012. FILE PHOTO

Next week, in the second instalment of The Kale Files, we will show how the sum of parts of Uganda’s security architecture worked to install Gen Kayihura as an unapologetic enforcer of the NRM regime, leaving Opposition stalwarts like Dr Kizza Besigye caught in the crosshairs.