Prime

Survivors of Mukono school fire narrate ordeal

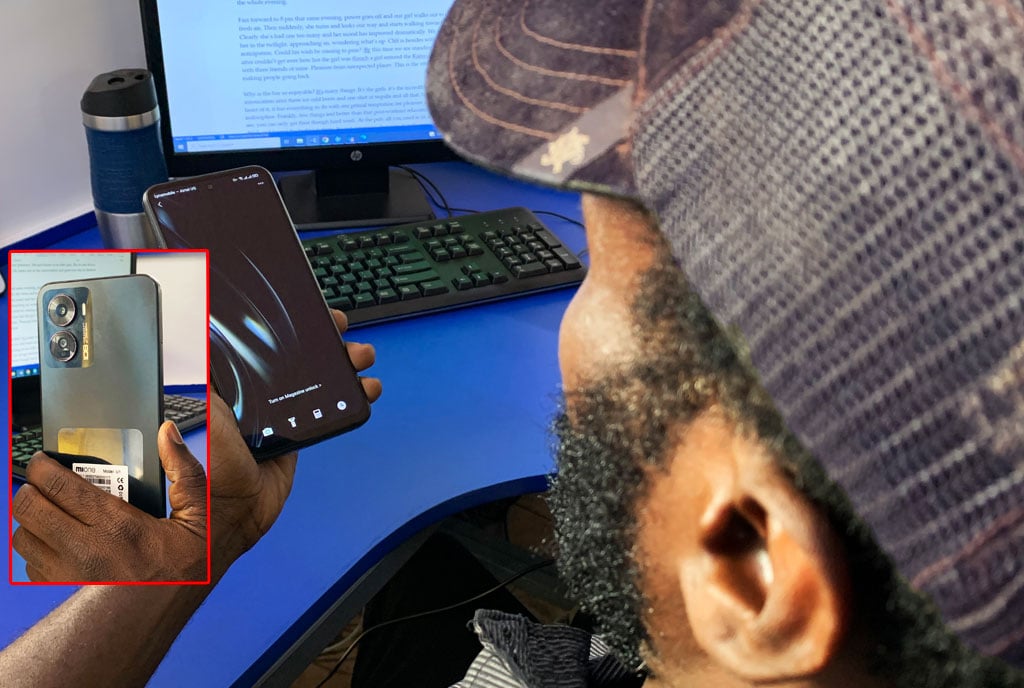

Maria Naganda, a Primary Four pupil and one of the survivors, narrates the ordeal. PHOTO/DOROTHY NAGITTA

What you need to know:

- Anyone suddenly woken up from sleep by screaming, shouting and smoke would struggle to find their way to safety in the dark dormitory.

A cloud of expectation had descended on Salama School for Blind on Monday. The Mukono District chairperson, Mr Peter Bakaluba Mukasa, had visited ahead of a visit by Princess Anne of the British Royal Family, scheduled for later this week.

After supper, the pupils, as usual, retired to their dormitories to sleep. Children being children, lights-out did not immediately translate to lights-out, recalled Juliet Navuga, a Primary Five pupil.

Mukono school fire:Pretty Parwoth, 13, died while saving others

In the warm dark night, between girlish giggles and half-suppressed chuckles, Gladys Namugga, another student, retold a story told to her by her parents during the coronavirus lockdown. Usually, the stories tapered off as one pupil after another finally drifted off to sleep.

But the cloud of expectation would soon turn into a raging storm of scorching desperation. Shamim Babirye, also in Primary Five, had drifted off to sleep when she was awoken by a shrill wail from one corner of the dormitory. The night air was suddenly rent by shrieks and screams, and the pungent smell of smoke.

“We tried to move towards the door,” Babirye recalled, “but there was a bed blocking us from accessing the door.”

SEE PICTORIAL: 11 killed in fire at Uganda school for the blind

Maria Namaganda, a Primary Four pupil, was initially frozen to the spot by the shouting and confusion, unable to make out what was going on. She was stirred into action by another pupil, Pretty Parowth, who frantically urged her to find her way out of the dormitory. “I was saved by her,” she said.

Anyone suddenly woken up from sleep by screaming, shouting and smoke would struggle to find their way to safety in the dark dormitory. For the visually-impaired students at the school, fate – and perhaps human neglect – had conspired to deal them a fatal hand.

Topista Nanyonjo says the fire appeared to have started from one of the lower beds near a dormitory window. The sleeping pupils on and next to that bed stood no chance.

Other pupils recalled hearing those on upper bunk beds falling off in agony as they tried to escape the inferno that was now eating through the mattresses and beddings.

Those who made it to the windows found that they were barricaded with burglar proofing – despite a government directive, following previous school fires, to have them removed.

Eva Nakimuli, a Primary Two pupil, said she was saved by a teacher who grabbed and threw her outside. Others were not so lucky.

Parowth, who had warned Namaganda to get out to safety, was one of them. She reportedly succumbed while saving other pupils, especially those in Primary One, who were crying in the dark.

Almost a quarter of a century after Yvonne Namaganda was martyred while trying to save her fellow students during a fire that killed 20 pupils at Buddo Junior School in 2008, another name was added to this soot-stained list of involuntary heroes.

The embers of reform lit during subsequent school fires had been reduced to the ashes of neglect and inaction. With the death toll rising, the policy post-mortem began almost immediately.

“The windows had burglar proofs,” the junior Cabinet minister in-charge of Disability Affairs, Ms Hellen Grace Asamo, said helplessly, and unhelpfully, at the scene on Tuesday. “And this is against government policy on boarding schools. The windows are not supposed to have burglar proofs.”

After the inferno swept through the pupils, the shock wave shifted to the parents. One parent said he learnt about the fire when he telephoned to school to ask about a visitation day earlier scheduled for Sunday.

As news filtered through, others, fuelled by hope and fear, rushed to the school for news or to collect their children. Agatha Nakalema, whose daughter survived, said she couldn’t leave her child alone. “I have to take my child home so that I can counsel her,” she said. “I see she is a bit confused.”

With Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) around the corner, school authorities were caught between a fire and government policy.

“We cannot close the school given that we don’t have any alternative to it,” the Mukono Resident District Commissioner, Ms Fatuma Ndisaba, said. “These pupils are supposed to sit their PLE in two weeks’ time. We appeal to parents who are picking these pupils to return them after two or three days because they also need counselling.”

She said they had asked the police to deploy more officers at the school, and had also sought financial assistance from the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) to pay for DNA tests to identify the victims and their burial expenses.

Students from far-flung parts of the country remained at the school on Tuesday, shaken.

“We shall wait for a communication and will see if we are to bring them back,” Alice Nakimuli, a parent who took away her child, said.

At the school, parents and relatives of the children huddled in small groups as police officers loaded charred bodies of the victims into waiting ambulances. One of them was Susan Adiru, Parwoth’s mother.

“We feel so saddened by this incident,” she said softly. “It’s very unfortunate.”

As investigators begin to sift through the ashes for remains and answers, many questions remain. Did the matron abandon her post, as Minister Asamo suggested, when the fire started?

Did the school, founded by the government in April 1999 with a vision to bring education services closer to visually impaired children, have any fire-fighting protocols or equipment? Were they followed? Why did the dormitory windows still have burglar proofing bars? Will the Royal visit go ahead? Have any lessons been learned from all the previous school fires? How many fires do we need to learn from history?