Prime

Dorm names and students’ intellects

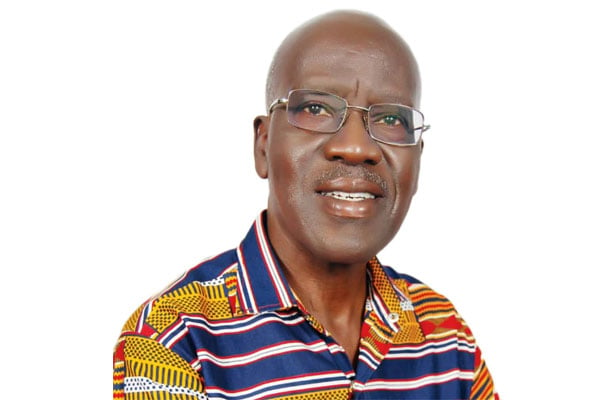

Prof Timothy Wangusa

What you need to know:

- Easily the most inspiring of these dormitory names was that of Aggrey.

You may change the name of a flower but its smell will remain the same.’ This is my paraphrase of William Shakespeare’s well-known quote, ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ True or not true? Shakespeare’s context was a young man and a young woman in love, whose families hated each other; and the young woman (Juliet) wished that her lover (Romeo) could change his family name – then, without changing his essence, he would be accepted by her parents as her lover.

What about students’ dormitories, halls of residence, and hostels – do their names have any particular bearing on the developing intellects of their occupants? Is one dormitory or hostel name or hall of residence name as good as any other? Or could, for instance, a sudden change of name of a students’ habitation as suddenly or perhaps gradually bring about a change in terms of self perception by the said student inhabitants?

While ruminating on this matter, my mind went on an anti-clockwise flight back to the first time I lived in a dormitory and, on the return journey to the present, it stopped at the other three subsequent institutions of classroom education where I progressively lived in a dormitory or its more mature equivalents.

In each case, my now antique mind noted the possible deliberate intentions of the dormitory name-givers and the possible, if infinitesimal but incremental, impact upon the dorm occupants during those years of still developing bodies and intellects.

At Masaba (Junior Secondary) School of the 1950s (in the then Bugisu District), every single dormitory was indigenously and exclusively named after one of the peaks or ridges of Masaaba’s Mountain (or Mount Elgon): Wagagayi, Zesui, Wanale, Bulago, and Namsindwa. For thus ignoring mountain peaks and ridges from other parts of the country or the world, the initial name-givers might be accused of overtly inculcating parochialism in the students, but there was the simple logic of educationally beginning with the local rather than the global. And for us students, there was the unspoken inspirational message of our being intellectually influenced and propelled upwards, towards the heights of the land, not into its valleys!

By comparison, with its motto of ‘Onwards and upwards’, you would have expected Nabumali High School of the 1950s and 1960s to have upward-tending names for its dormitories; but instead it had names of personalities. Unlike the government-founded and non-denominational Masaba School, Nabumali High School was the brainwork of British missionaries of Church Missionary Society (CMS). Throughout Uganda, CMS-founded schools were known as NAC schools, the latter initials standing for ‘Native Anglican Church’ – and one must wonder how a Christian denomination which was sown into the soil of England and germinated there (in 1533 AD), could be described or contrived as being ‘native’ to Africa!

But it was as an NAC school that Nabumali High School chose to name its dormitories after eminent Anglican missionaries, two eminent Ugandan churchmen, and one eminent Ghanaian educationist. The Anglican missionaries were Bishop Hannington, Crabtree, and Banks. And the three eminent Africans were Apolo Kivebulaya and Bishop Stephen Tomusange, both of Uganda (Anglican) and Ghana’s Aggrey of Achimota (Methodist). And there we were, in contrast to Masaba School, no dormitory name from the immediate environment, and a good half of them from beyond the seas.

These eminent Christian personalities indeed served as more than dormitory labels; they were also vaguely inspirational names. We each grew to be proud of our allocated dormitories, as may be currently attested to by the Old Students’ WhatsApp social groups fondly based on the individual dormitories.

Easily the most inspiring of these dormitory names was that of Aggrey. Born in Ghana and ending up in America, Dr Aggrey of Achimota is famous for several uplifting quotes, including, ‘…educate a man, you educate an individual; …educate a woman, you educate a nation’.

Prof Timothy Wangusa is a poet and novelist.