Prime

Let me ask a simple question: What does Gen MK stand for?

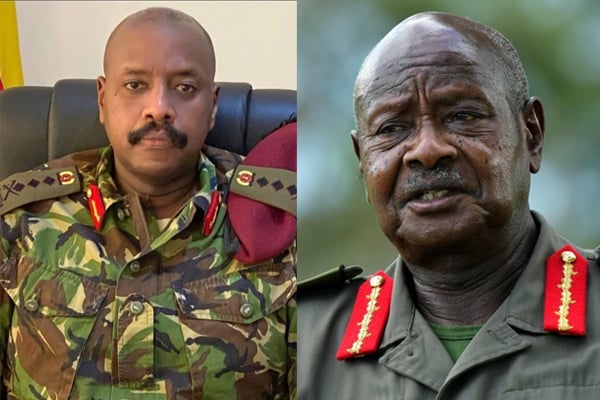

Author: Asuman Bisiika. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- To project some kind of national consciousness, I would like to invite Team MK to adopt the idea of holding a national dialogue as their political position.

Since November last year, I have been struggling with ill health. However, even in my condition, I have been steadfast in my request from God: just delay my departure so I can witness Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba as President of Uganda.

Gen Kainerugaba wants to be President of Uganda and he seems to be in a hurry. And then a friend who erroneously thinks I could be familiar with the MKPA (Muhoozi Kainerugaba Presidential Ambition), taunted me: “But Asuman, let me ask a simple question: what does ‘your’ Gen MK stand for? He is just high on unstructured rhetoric and low on policy outlays. He sounds like the other guy who could not articulate fiscal policy proposals.”

I must confess, my friend’s query made me feel very dry in the mouth. “If God must delay ‘my total recall signal’ to allow me witness the Muhoozi presidency… Yes, what does Gen MK stand for?” I challenged myself.

**************

Because of my limited movements these days, I have been watching The Lion King several times. The near-comical and animated character-build of the actors has not distracted me from picking or even identifying with themes associated with the challenge of leadership.

Uganda has been an independent country since Tuesday October 9, 1962. However, more than 60 years after independence, all the political efforts aimed at nation building have not yielded tangible and sustainable value systems to build a national political culture and consensus.

The political history of Uganda reads like a case study in a crisis of confidence; with brutal armed conflict as a sub text. And with such a crisis of confidence, building a national consensus to rally the population has eluded the ekolo (Lingala: the nation).

The view that electoral processes would bring the much needed national consensus has fallen flat. For good measure, Uganda has now held six consecutive national elections since 1996. If one added the election that brought the first post-independence government in 1962 and the famous 1980 elections, Uganda is likely to be one of the very few African countries that have held more than five multi-party elections.

Yet all of those numbers of elections add up to nothing; because they have always attracted the tag of ‘disputed elections’. Indeed, a serving general talking or twitting about his or her future presidency would not be assumed to be talking about electoral processes. He or she would be talking about the presidency in a more ‘fiat-ish’ way than the formal way of becoming president.

Most Ugandans now seem to have come to the conclusion that elections alone are unlikely to produce the much-needed and elusive national consensus. That’s why Ugandans now have minimal confidence in electoral processes as a source of a national consensus behind which to rally the population and national vision.

With this state of affairs, most Ugandans would espouse the idea of a national dialogue as a basis or platform from which a national consensus would be generated to rally the population.

After the 2011 and 2016 elections, it became apparent to most Ugandans that elections would not be the main instrument to build a national consensus. And the idea of seeking alternative tools was born. One such tool was a national dialogue. To project some kind of national consciousness, I would like to invite Team MK to adopt the idea of holding a national dialogue as their political position.

May be then my friend’s curiosity about what Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba stands for would be satisfied. May I also take this opportunity to offer my unsolicited advice to those around the good general to craft a message broader than his rhetoric on ‘generational leadership.’

Mr Asuman Bisiika is the executive editor of the East African Flagpost. [email protected]