Prime

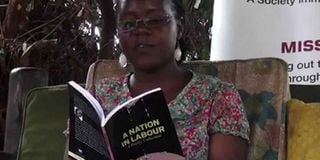

A Nation in Labour: Meet Harriet Anena

What you need to know:

- A most potent poetic voice from Acholi, Anena was born almost 50 years after Okot p’Bitek; and about 50 years separate the publication of Song of Lawino and A Nation in Labour.

- But Anena is no outgrowth of the ‘Okotian Song School’, as characterised by the prolonged dramatic monologue of the protagonist of a given ‘song’ or long poem.

When a nation is in labour, what do we expect next? That it will soon give birth to its baby. And how soon is that? And what kind of baby is to be expected? And is it one baby, or two babies, or perhaps many more? Healthy or deformed babies? For a proper answer, ask Harriet Anena!

And who is Harriet Anena? She is the extremely talented poetic weaver of words into poignant messages of pain and pleasure who, together with her co-performers to the accompaniment of Ugandan musical instruments, wowed captive audiences at Uganda’s National Theatre for three consecutive evenings, (June 28-30). ‘Your truly’ was in the audience of the first performance.

Born in Gulu District, Uganda, Anena holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Mass Communication from Makerere University. She worked with the Daily Monitor newspaper as a reporter, sub-editor, and deputy chief sub-editor from 2009 to 2014. Anena wrote her first poem, The Plight of the Acholi Child’, in 2003. It won a writing competition organised by the Acholi Religious Peace Initiative, and it helped to secure her a bursary for her A-Level education. Since 2013, she has steadily written one publishable poem or story after another.

Anena’s poetry collection, A Nation in Labour (2015), won the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa for the year 2018. She was named joint winner of the prize with Prof Tanure Ojaide, a well-established poet from Nigeria. The prize is named after Wole Soyinka (b.1934), Africa’s first black Nobel Laureate in Literature, 1986. The biannual prize is a ‘pan-African writing awarded to the best literary work written by an African.’

Regarding the context and content of her writing, the poet has stated: ‘I explore my experiences as a child who lived through the LRA insurgency in northern Uganda and the post-war period. Today, I still keenly watch how people are piecing back the torn pieces of their lives; but also the post-war challenges such as child-headed homes, land disputes, crime, alcoholism, etc.’ The performance of Anena’s poetry on June 28 comprised four interwoven segments:

The LRA war in northern Uganda; a traditional countryside romance; portrait of a normal ‘manly man’; and the current Ugandan political status quo. Expertly directed by the playwright Deborah Asiimwe Kawe, the performance was extremely powerful and elicited very warm compliments from the rapturous audience. Lasting no more than 60 minutes, the performance was followed by an animated discussion and interaction time between the performers and the audience – somewhat reminiscent of the classical Greek ‘symposium’, an ‘after dinner conversation’.

Our dinner in this case, after which we sat back and talked, was this three-course ‘Anenaic’ kwon dish, for which the sauce was the accompanying music of the talking instruments.

A most potent poetic voice from Acholi, Anena was born almost 50 years after Okot p’Bitek; and about 50 years separate the publication of Song of Lawino and A Nation in Labour.

But Anena is no outgrowth of the ‘Okotian Song School’, as characterised by the prolonged dramatic monologue of the protagonist of a given ‘song’ or long poem. On the contrary, Anena is forging her own poetic mode as a writer of the short lyrical poem that is imbued with tremendous energy, graphic home-grown imagery, subtle allusions, and exquisite humour.

For me, the Anena performance confirmed three personal theories of mine about the essence of poetry, the significance of performance, and the fundamentality of poetry. The essentials of poetry – word economy, figurativeness, and musicality – are all there in Anena’s verse. She also signals that the future survival of all forms of literature lies in performance. And she proves that poetry is the mother tongue of all of us!

Prof Timothy Wangusa

[email protected]