We must do something about Sickle Cell Anaemia

What you need to know:

- Let us not fold our hands but we must do something about sickle cell anaemia in Uganda and defeat it together.

At the weekend, the fraternity of doctors was again hit by the loss of another medical student, Edgar Nsumba, from Sickle Cell Anaemia. Earlier on Friday, Edgar took the last of his fourth year. As fate would have it, he deteriorated rapidly and died shortly in the evening. This is the fourth such death of medical students, intern doctors or a fully registered young doctors in the past two years from sickle cell anaemia.

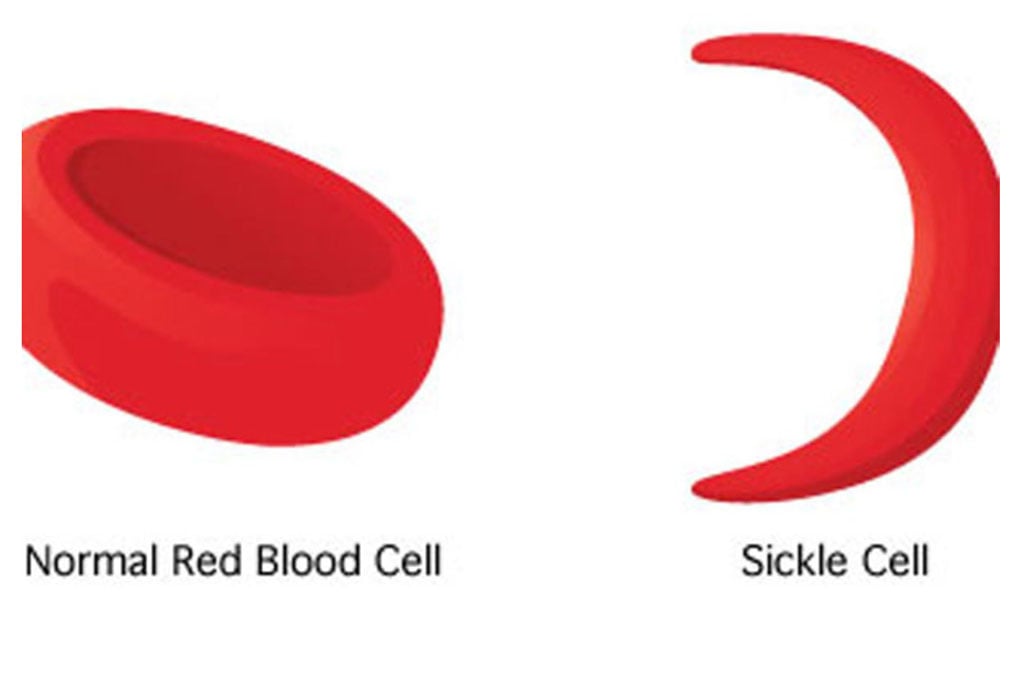

Sickle cell anaemia is an inherited disease of the blood pigment, haemoglobin, found in red blood cells and which transports oxygen in our body. In Uganda, one of every seven persons carry this gene and 0.8 percent have the disease. Annually, 20,000 children are born with the disease. Affected persons have two abnormal genes inherited from each parent. Those who inherit one copy do not suffer the disease but are carriers.

Sickle cell anaemia already contributes over six percent of child deaths in Africa. In Uganda, it is now a leading cause of child deaths. .

In the first three to six months of life, all babies have fetal haemoglobin, HbF. Beyond this age, they take the normal adult haemoglobin, HbAA. In people with sickle cell anaemia, this is replaced with HbSS. Babies develop painful swellings of the hands, fingers, feet and toes. They may experience life threatening rapid enlargement of the spleen, pooling blood and severe anaemia. This can lead to death rapidly. They may experience severe life threatening bacterial infections.

Beyond infancy, there are repeated painful episodes of the limbs, chest, back and abdomen. They may have massive red cell destruction, the eyes become yellow and develop severe anaemia. Again, severe life threatening infections may occur together with painful and prolonged erections, sudden difficult breathing called acute chest syndrome, kidney, and heart damage. Older children may present with poorly healing wounds, stunted growth and the worst, repeated stroke. The complications are so many and severe that in the past, over 80 percent never made it to the fifth birthday.

I am leading two research projects on sickle cell anaemia – one at Mulago to examine the prevention of the devastating strokes and the second in Jinja and Kitgum hospitals to find better medicines to prevent malaria.

Last Monday, I was in Jinja to attend an ethics committee inspection. The study clinic was flooded with very sick children. The verandah, corridor, clinical and emergency rooms, labs and an extra tent were full with malnourished children arriving with yellow eyes, writhing in pain and fever. We have so far lost five children of the 430 children we recruited to sickle cell anaemia complications. Although this is a marked improvement from the 10-20 percent annual deaths, this state of affairs cannot continue.

We should arm ourselves with knowledge about sickle cell anaemia, its complications and care, especially appropriate home care such as adequate hydration, and the importance of vaccination and research.

A few years ago, a study led by my colleague, Prof Robert Opoka, demonstrated that if taken daily, the medicine hydroxyurea markedly reduces ill health. Patients had fewer painful episodes, fewer transfusions and hospitalizations. The medicine costs only Shs1,000 daily. We must make it available to every single child with sickle cell anaemia in Uganda.

If you have a child with sickle cell anaemia, arm yourself with knowledge. Ensure they receive all childhood vaccinations on time and sleep under mosquito nets. They need daily folic acid, much more fluids, protein, and energy foods and should be dressed properly in cold weather. They should not play in hot weather for long. We also give them medicines to prevent malaria and others to prevent bacterial infections.

But we need to do more. The gene is so prevalent in Uganda that all of us should test and know our status. With each pregnancy, two married carriers have a 25percent chance of producing a baby with sickle cell anaemia and 50 percent chance of producing a carrier. This cannot continue.

We have about 1,200,000 births in Uganda annually. All should be tested at birth and started on treatments early. The infrastructure is available through the National Public Health Labs and is possible. Beyond this, we should begin to have the difficult discussions. I am imploring our leaders in churches, mosques, the media, civil society, political leaders and health workers to talk about sickle cell anaemia. I know two doctors who broke their engagement just before their wedding because they found out they were both carriers.

I urge the government to introduce a bill or an individual MP, a private members bill on sickle cell anaemia in Parliament to address this problem. Let us not fold our hands but we must do something about sickle cell anaemia in Uganda and defeat it together.

Associate Professor Richard IdroConsultant Paediatrician and Immediate Past President, U.M.A