With Tabu Ley goes a legendary Soukous era

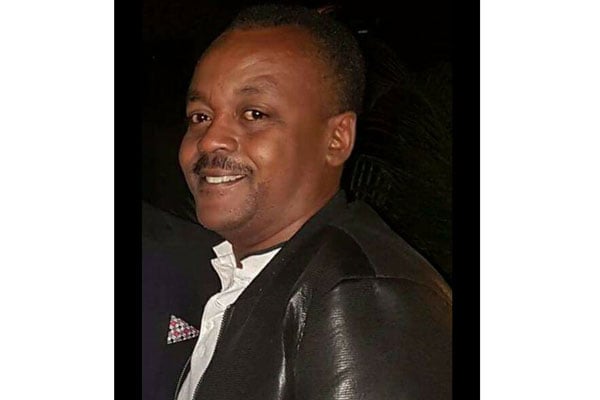

Tabu Ley during a performance. He died on Saturday in a Belgian hospital. Internet Photo.

What you need to know:

Long before Fally Ipupa, one man dominated the soukous music scene. Tabu Ley Rochereau was his name. He died on Saturday, November 30.

Out in the open yard, sometime in the 1990s, a couple of naughty children may have run about, chasing one another, screaming, chanting, singing. They could easily have been singing along to the soukous hit, Muzina, blasting through the windows, from a Panasonic stereo system, somewhere in the house.

And you would want to condemn their mischief, for as they sang along, they weighed their lines, heavily, with tinges of innuendo, sexual innuendo; the song’s title also passes for a sexual description, in colloquial Luganda.

For the generation that only knew Tabu Ley Rochereau, born Pascal-Emmanuel Sinamoyi Tabu, post 1990, Muzina is by far, his most identifying tune, in the Ugandan market. But by the time he released that deeply religious and spiritually toned song in 1994, the towering figure of a man, with prominent facial features – large nose, flabby cheeks and full lips – had charmed and waltzed his way into the hearts where Soukous music was more than just sound, but a dose of soothing balm.

By then, Tabu Ley had already done his part in headlining the export of soukous music, to the region beyond the Democratic Republic of Congo, including but not limited to Uganda, stretching all the way to Europe and North America, raising it as the foremost, definitive African sound.

And by the time the curtains fell on a life not wanting of either achievement or fulfilment, the young boy who named himself after French army General (Pierre Denfert-Rochereau), while still a teenager, had gone on to sing, write and produce songs, nurture and apprentice a new generation of soukous stars, and crown it all by retiring to the less artful life of politics. Tabu Ley Rochereau died Saturday, in a Belgian hospital, after an illness resulting from a stroke he suffered in 2008.

His music

For a man with such physical presence, it was quite something that when he stepped to the microphone, the output was a mildly soft set of vocals that he often twisted to good effect, to achieve a catchy tenor.

His earlier songs, like Molangi ya Malasi and Ya Gaby were much slower, with strong latino and salsa influences, and they illustrate the nature of soukous at the time. But as if to keep up with the changing face of a genre he helped create, his later songs, like Ibeba, Amilo and yes, Muzina, picked up the tempo. These started with a slow rhythm, followed by a mid-tempo midsection and then an all-systems-go final third, the sebene, where the guitars went wild and raged, and queen dancers invaded the stage to much applause. This, also, partly engineered by Tabu Ley, became the defining feature of soukous, until later musicians like Awilo Longomba reduced it to a sebene-only affair.

The generation that heard him

For the Ugandans who were lucky to watch him perform, the energy of his performances was simply infectious. “That was one of the guys who really got me interested in music,” says city businessman and pastor, Peter Sematimba. “I remember I attended one of his concerts here in the 1970s during the Idi Amin days while I was still a little boy. He seemed like an incredible dancer. His queen dancers were dressed in bikinis with sisal skirts, and every time they moved, you could see every part of their body move. It got the crowd really excited,” he adds.

Robert Kalumba, a communications professional in Kampala, salutes Tabu Ley for having broken ground in selling raw African music to the West, at a time when Europeans did not understand African languages, and the disparity between the two continents was greater than it is now.

Kalumba also praised Tabu Ley for his music writing sense. “Their songs talked about the big issues of the day that people of that time were facing. They were not like us now, singing about Coccidiosis,” he says.

Sematimba names Tabu Ley as one of his 10 major players in Soukous, describing him as a “solid singer with great vocal control.” Kalumba says, “It is sad for African music, tradition and culture, that we are losing such people. His generation of music has passed on and will not be replicated.”

Tabu Ley’s star shines up there along that of artistes like Franco, with whom he shared a healthy rivalry and working relationship. The two were the front acts of a genre when it rose to gain international acclaim. They led the way for artistes like Madilu, Koffi Olomidde, Mbilia Bel and Kanda Bongoman to rise and shine.

Tabu Ley leaves behind a world that has far moved on from the one that easily put everything they did aside, to catch a second of his soukous tunes. Where Franco and Tabu Ley once stood, now Fally Ipupa stands and weaves his magic. Once in a while, when tuned in to an oldies’ show, a cheeky fellow may sing along to Muzina, not for the religious praise to God it spreads, but for mischief. Today’s generation would rather reach for the remote control and change channels once a Tabu Ley song queues as next to play.

The artiste may now seem like a long lost voice, drifting away, in the wind. But that wind will stand around for much longer after he is gone, as a tribute to a man that did his part in giving humanity a music genre.

Tabu Ley at a glance:

• Born Pascal-Emmanuel Sinamoyi Tabu November 13, 1937, in a small village in the western Congolese province of Bandundu.

• Sang at church while still a child and nearing the end of his High School, joined the African Jazz band.

• Trained and later had a relationship with musician, Mbilia Bel. The two had a child but separated.

• Left the DRC (then Zaire) into exile in 1988, returning in 1997 to serve as a minister in Laurent Kabila’s regime.

• Stayed in politics until 2008, when he suffered a stroke.