Prime

The folly of forming a political party

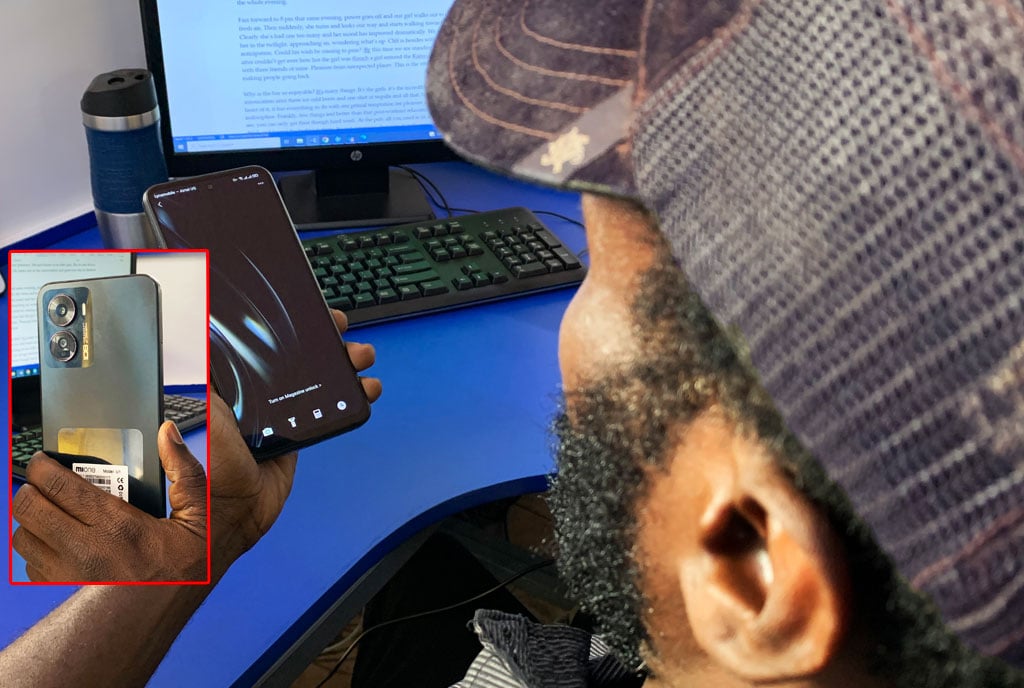

Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- To form a political party and run for office at best helps legitimise the status quo thereby contributing to its continuity.

Sections of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), including its founding president, the indefatigable Dr Kizza Besigye, are reportedly mulling forming a new political ‘outfit’, a political party. Wrong idea!

From 2006 to 2021, for what it was worth (not a whole lot, really), the FDC was Uganda’s leading opposition party, supplanted by the new kid on the block, the National Unity Platform (NUP) led by Mr Robert Kyagulanyi in the wake of the last election.

NUP was cobbled together at the last minute out of the ‘People Power’ movement. Its utterly surprising sweep of parliamentary seats in central Uganda catapulted NUP, overnight, into the main opposition party with the legal and constitutional mandate to lead the opposing side in parliament, again for what it is worth (not much, to be sure).

For individuals who, in all fairness, are now veterans of opposing the rulership of Mr Museveni and his NRM state-party, Besigye and company should know better that Uganda’s problems is not the dearth of political parties, rather the death of a culture of multiparty politics.

Those who closely follow what has transpired recently need no reminding that the faction of FDC led by Dr Besigye and Kampala Lord Mayor, Mr Erias Lukwago, are in the political cold of sorts, estranged from their party and its headquarters at Najjakumbi because of alleged sell-out to Mr Museveni by the incumbent party president, Mr Patrick Amuriat, and secretary general, Nathan Nandala Mafabi.

This allegation, true or false, is not entirely unfounded or without precedent. If indeed Mr Amuriat and Mr Mafabi made a deal and took so-called ‘dirty’ political cash, thus compromised, it may be disappointing but certainly not surprising.

The modus operandi of Museveni’s rulership, indeed of most authoritarian regimes, is to scatter the opposition through a range of tactics and operations including overt financial inducements and appointments. This has already been applied to Uganda’s two oldest political parties, the Democratic Party and the Uganda Peoples Congress. If it is done to FDC, as alleged, that would be a continuation of long-standing practice.

There are hushed tones about similarly compromising infiltration of the NUP. There is absolutely no guarantee that a new political party will not be preyed on by the same debilitating and destructive machinations that all credible and consequential parties have experienced.

When Ndugu Mugisha Muntu left FDC to found the Alliance for National Transformation (ANT), I thought it was a misstep. I still believe so. That party’s utter invisibility, not to mention the patently poor showing in the 2021 elections, just underscores why forming a new political party isn’t what is needed for those committed to bringing to an end the current broken political system and mal-governance.

The same way the DP and UPC were long demobilised, FDC ripped apart and rendered pretty much irrelevant, and NUP likely on course to being nipped is, without a shed of a doubt, how another serious political outfit, functioning as a political party, will be tackled by the rulership.

I have always made the case for political parties. I still believe that organised and structured political engagement through formal and institutionalised channels, of which a political party is a key actor, provides the best way of managing national politics and advancing the agenda of accountable and responsive leadership.

This is far better than the retail politics of individual power brokers and personalities that often end up interested more in personal aggrandisement than the public good for society.

But I am also acutely aware that political parties do not operate in a vacuum nor can they function under any conditions or circumstances.

There is a case to be made for the necessity of a political party as a vehicle for electioneering even under the unconducive and hostile environment of authoritarianism, as we have in Uganda today.

In fact, participating in and contesting elections is critical to the struggle for attaining the desirable democratic government that progressive forces are committed to.

Yet, we also know that individual interests in running for office, say as a member of Parliament, tend to trump the broader cause of changing the system and bringing about fundamental change. The shenanigans in Parliament, with opposition MPs at fault for partaking in the orgies of financial abuse and dancing to the lyrics of the rulers, just underlines the perils of faith in minimalist opposition electoral success in an authoritarian system.

A more compelling case for the forces of change, those Ugandans seeking to rewrite our present script and help fuel our future, is to work towards a national movement for change that will as a matter of urgency midwife a new political system with a new social contract.

To form a political party and run for office at best helps legitimise the status quo thereby contributing to its continuity.

This helps a few selfish individual political entrepreneurs to cash in on the national coffers: MPs, district chairpersons or ‘opposition’ leaders. In the broader scheme of things though, a new political party scarcely benefits the cause of good government.